Longread

Making ‘water and soil’ a guiding force in planning in nine rounds

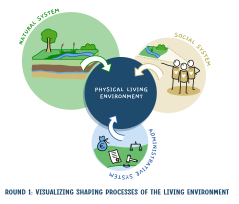

The effective application of the policy intention 'water and soil driven' in the Netherlands requires a different approach to Dutch planning; from structure planning to system planning. Wageningen Environmental Research (WENR) proposes an approach to spatial planning based on the three subsystems that form our living environment: the natural, the social and the administrative subsystems. In this way, we want to contribute to an answer to the question of how water and soil can play a prominent role in the spatial planning of the Netherlands.

The approach of WENR in collaboration with GrondRR is based on the vision that landscapes are shaped by the interaction of the natural, social and administrative subsystems. You can make ‘water and soil driven’ concrete in a collaboration by taking the system as a starting point, dissecting it into the three subsystems, understanding the processes within and between them and establishing important values for the future of the area. Thereafter you can formulate design principles for the area and gradually integrate the insights obtained. In this way you can develop a future-proof vision, an implementation strategy, and development paths resulting in measures in time and space.

The challenge

An area is formed by the interplay between the natural system and our interests as individual and society. For ages, spatial development remained within the carrying capacity of the natural system; water and soil guided where and how cities emerged and what form of agriculture could be performed successfully. On the one hand, this limited our options for living and working, but on the other hand, the natural system continued to function and was able to supply ecosystem services like clean water, fertile soil and healthy air. With the arrival of more technical solutions we were able to increasingly control our natural environment resulting in the degradation of the natural system. In the Netherlands, water management, land conversion and intensification of agriculture have significantly altered much of the country. And now we are in a situation in which the natural system has been damaged, spatial planning is at a standstill and the existence and severity of the climate, agriculture, housing, water and biodiversity crisis are widely recognised1. The question is how we move to a more healthy living environment in the future, based on the natural system2 with a sustainable economy where land use can evolve with the future challenges.

The conditions

The approach that we propose here starts by forming a group of key individuals and organisations to start a co-creation process. We bring together participants who have sufficient resources and mandate to bring this forward. In addition a number of ingredients are crucial:

- A shared view of the challenges and a system approach. Stakeholder involvement is crucial in this process; the people who use land or have an interest in it for other reasons. We must start working more from long-term thinking and from the coherence of the subsystems. In other words: the importance of a systems approach must be recognised. If this realisation arises, it will form the driving force behind the system-oriented process of landscape development towards a healthy living environment.

- A flexible and reflective process. It is important to create space to deal flexibly with unexpected developments. In practice, things may not always work out as planned. To achieve this flexibility, it is necessary to keep the door open to alternative visions of the future in case the world develops differently than expected. Or if the actual implementation turns out to be more difficult than expected. Therefore, you can designate and agree on selection moments in advance. So, the direction is clear to everyone and trust can be created; the joint effort is not without obligation. To monitor whether goals are achieved you can learn and adjustments can be made where necessary. This also includes that you keep checking whether you have the right people at the table for that phase in the process and to involve others if necessary.

- The importance of guarantees during the process. During the process, commonly shared insights and principles arise. It is important to record these shared principles, development principles and visions during the process in a document that that is adopted by the area. This could be a memorandum, a manifesto, a policy document, a vision, policy line or perhaps even a law. This provides clarity and security for taking the next steps.

- Transition is construction and destruction. The change needed to become more ‘water and soil driven’ requires a fundamental change - in social sectors and in planning practice. Too often, reasoning is still based on the short term and on the basis of current interests. The result is that harmful practices are made a little less harmful, or bottlenecks become a little less tight.

We are optimising current land use practices. This makes it increasingly difficult to implement substantive changes in land use and land use planning - while the solution to the multifaceted, interrelated problems we are now facing requires a fundamental change. This requires phasing out certain existing practices, which may cause problems for stakeholders in the short term. We should not ignore these, but discuss them and solve them or make them bearable. We must work on a future dialogue and make (mental) space for a vision of the future that offers perspective for all stakeholders.4

Stepwise approach

We present a system-oriented method that offers tools for effective integral planning. The aim of the approach is to be able to create a healthy living environment that functions more naturally and is resilient.

This methodology comprises nine rounds, which do not have to be completed linearly. It is rather a matter of moving between the rounds and working in different cycles. This allows new insights from one round to be integrated or tested in another round, at a different scale level or in a different subsystem.

The three subsystems

- The natural subsystem

- This refers to the natural water and soil system, the associated ecosystems and the natural processes, including living nature, that are formative in this.

- The social subsystem

- This concerns the people who live, work or otherwise have an interest in the area, the skills, habits and customs that they have developed there over the course of history, their culture, the meaning they give to the living environment and the way in which they use it and have shaped it liked they wished.

- The administrative subsystem

- In this subsystem, the ambition to make water and soil driving must be shaped and therefore we consider it separately from the other two subsystems as it is of a slightly different nature. It arises from the social subsystem and leaves its mark firmly on the natural, physical landscape. This applies to both formal aspects such as legislation and regulations, policy and forms of government, as well as to more informal agreements, customs, habits and governance that guide human behaviour and its spatial impact.

These 3 subsystems result in the physical living environment of people and society. We form the natural subsystem into our living environment partly via the administrative subsystem.

1 Visualising shaping processes of the living environment

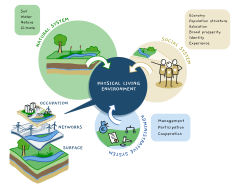

We constantly adapt our living environment, in land use, in management, and also via planning processes at different scale levels. In order to make water and soil more guiding, it is valuable to divide the current landscape into three subsystems to consider these separately and to map processes that shape the living environment to integrate the insights round by round (see box).

Relation to the Dutch layer approach to spatial planning and design

Various aspects of the subsystems and of the resulting living environment can be represented as map layers in an area atlas. The aspects of the living environment can be classified according to the layers of the Dutch layer approach. However, this classification is different than the classification into the 3 underlying subsystems. In distinguishing the three subsystems, we emphasise understanding the shaping processes on the living environment. The layer approach focuses on the relationship between the various ‘layers’ of the landscape. It places more emphasis on the difference in dynamics of processes and the time scales on which they occur in the various layers of the landscape. The nature of the shaping processes in the social and administrative system on the living environment receive less attention here.

2 Understanding the subsystems

It is important to analyse each of these subsystems, both the components and the coherence, and to recognise important processes in them. That is why it is important to look at the area at a higher scale level; after all, a landscape or region never exists in isolation. For the process between the landscape now and later, it is important to be able to switch between the different scale levels. From international where applicable, to local in order to have a good picture of the differences within an area. In addition, it is also desirable to look at an area over time. How did it start, how did it develop? So, important guiding processes can be discovered in the development of an area, within and between the subsystems.

3 Appreciate: values and qualities

What are the crucial values in each of these subsystems currently and what is needed for the future? Economic value that is often expressed in money is important but incomplete. In this round, we will also identify the aesthetic and cultural values of an area, for landscape elements that are important for regulating processes in the landscape, such as the cleansing capacity of the soil, healthy water, pollination and soil fertility. What natural values and natural processes are important in the area? We will visualise these values and their importance and literally put them on the map. This also makes the coherence between values from the different subsystems visible.

4 Trends, bottlenecks and challenges

Based on the understanding of the subsystems and the values that have been established, we explore what trends and developments are relevant and identify bottlenecks and tasks for the future. Then we formulate desired development directions for various challenges by prioritising the development of the natural system as a basis for social challenges. This also strengthens biodiversity and climate adaptation. What tasks, then, are the most leading, where is the potential synergy between solution directions for various tasks and where do they get in each other's way? Sometimes it is useful to change perspective, and in addition to the strategic level, also to look at possible opportunities and bottlenecks at the tactical and operational level - as a reality check. It is important to keep this abstract and not to get bogged down in details.

5 Integral set of guiding principles

Based on the previous rounds, you can formulate an integral set of guiding principles for a vision of the future. It is important to formulate these principles broadly in close consultation with all actors. These principles function as starting points for the vision that we create in the next round.

6 Exploring different solution directions at system level

Based on the development principles, various solution directions are explored and elaborated for various sub-problems. Here we start to work in more details. We draw the solution directions on the map to make these spatially explicit. Then we decide what solution directions for various sub-problems fit together, where they can reinforce each other and where not.

7 Creating a guiding vision at the system level

In the previous round, a logical, coherent set of solution directions emerged that we will further elaborate into a guiding vision for the distant future that makes the best possible use of the strengths of the various subsystems. The vision shows what a healthy living environment for the specific area looks like, with attention to each of the three subsystems and the coherence between them, and must be recognisable for and supported by the parties in the area.

This is the phase of the creative leap5 that you make with research by design when you move from a phase of analysis to a phase in which design and visioning are central.

8 Developing an integrated strategy and development paths

The next question is: how do we get there? What coherent sets of measures can you define in this way, how do you plan them in time and space, and who is responsible for what? Other relevant questions are: how to manage, what and how to monitor and how to switch to a different development path6 if needed?

Still it is important to continue looking at different scale levels. For example, sometimes regulations on a national or international level obstruct a development on a regional scale. On the other hand, there may also be opportunities when visions or financing at other levels offer starting points. And it is also important to include the tactical and operational levels, in order to test the feasibility of the plan.

9 Establish agreements

Finally, all parties involved develop a strategy about measures, roles and responsibilities and how monitoring and adaptive management are designed. The strategy is included at the right scale levels in policy, visions of, or agreements between the relevant parties. This creates the link from the strategic to the tactical and operational level.

The way forward

The need to make ‘water and soil driven’ more guiding in spatial planning is becoming increasingly apparent. Recent policy attention in the Netherlands for spatial planning, for example by appointing a Minister of Housing and Spatial Planning in the current government, but also from the Spatial Policy Memorandum and the provincial approach to rural areas, means that there is now momentum to bring this intention into practice. On the European level, recent calls for a landscape approach, nature based solutions, integral water management, climate resilience and sustainable agriculture express similar attention.

We have developed this methodology as a framework for various methods, tools, data and maps. WENR has the intention to make information and tools accessible to a wider audience to improve spatial planning (see for instance: this interactive PDF (currently only in Dutch). WENR has the intention to make information and tools accessible to a wider audience to improve spatial planning. In the coming years, we will collaborate with a consortium of governments and other organisations to support this goal.

Verwijzingen

- For instance, refer to: ‘Water en bodem sturend’ vraagt om een brede blik, Grote opgaven in een beperkte ruimte,| Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving (pbl.nl), Ruimtelijke ordening in een veranderend klimaat Raad voor de leefomgeving en infrastructuur (rli.nl), and: Op Waterbasis : grenzen aan de maakbaarheid van ons water- en bodemsysteem | Deltares (Dutch)

- Also refer to: Laat natuurlijke processen hun werk doen. Daan Verstand, Sverre van Klaveren en Shannen Dill, RO magazine August 2024. (Dutch)

- View Homepage - KLIMAP: regionale aanpak klimaatadaptieve maatregelen voor hooggelegen zandgronden - KLIMAP: regionale aanpak klimaatadaptieve maatregelen voor hooggelegen zandgronden (Dutch)

- For instance, refer to: Focus op korte termijn hindert transitie landelijk gebied (Dutch)

- Such as EU Adaptation Strategy - European Commission, Sustainable use of key natural resources - European Commission, Nature-based solutions - European Commission