News

International wheat trade in times of war: seven questions and answers

The war in Ukraine has a major impact on the availability and price of wheat across the world. We talked about this in the national Dutch newspaper “De Financiële Telegraaf”. Now that an agreement in principle is being made between Ukraine and Russia on the passage of the grain across the Black Sea, major issues remain when it comes to the safety of the grain ships. For example, who is going to send the 300 ships of grain and can these ships still be insured?

In the meantime, the wheat is still waiting in the silos while the next harvest is already on its way. People are talking about a food crisis, but is this the right term? It is more of a food-price crisis, and some parties have earned a lot of money from it. What is this market like now? We investigate this by exploring seven questions.

1. Is there enough wheat in the world to feed everyone?

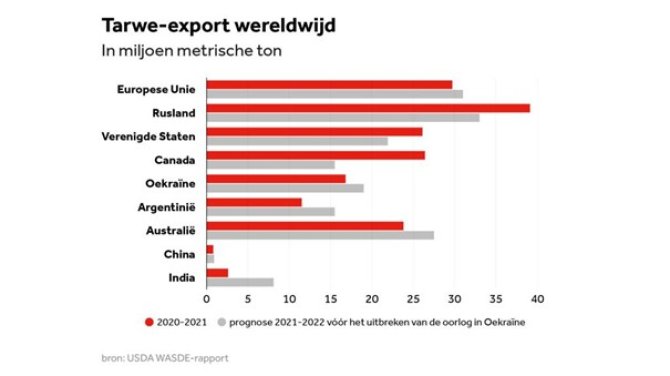

In principle, there is still enough wheat for the whole world. The spike in wheat prices and the blockade on relatively cheap wheat from Ukraine are causing the problems. Ukraine is by no means the biggest wheat producer in the world. The biggest wheat producers are China and India, but they mainly produce wheat for domestic consumption. Ukraine does have an important place on the list of the biggest grain exporters (although Russia, the US, the European Union, and Australia are at the top), and much of that wheat and maize cannot currently leave the country. Exports from Russia have also largely come to a standstill. Ukrainian and Russian wheat in particular dominated exports to the Middle East and North Africa, with relatively short transport routes. The importing countries are now dependent on other, much more expensive supplies.

The current problem for Ukrainian exporters is that they cannot get rid of their wheat due to the blockades and mines at the ports that are still in Ukrainian hands. At the same time, the next harvest is coming. The Ukrainian farmers and exporters are therefore forced to lower their price for the wheat that they have in their storehouse, but that does not help exports. With this as the status quo, wheat prices on international markets remain high.

Due to the much higher wheat price on the world market, importers also need more trading capital to buy wheat and ship it to their domestic markets. Often importers in certain countries (often in Africa) do not have sufficient trading capital to finance wheat transactions. This leads to absolute shortages on those national markets and further drives up the domestic price of wheat.

The winter harvests of wheat are now arriving in various countries, including Russia and the US. These harvests are better than expected and will bring the world market price for wheat down drastically again.

In short, there is enough wheat in the world in principle to feed everyone. However, the much higher price hinders consumers with low purchasing power from getting to that wheat. Locally, absolute shortages can arise due to a lack of trading capital among importing firms. New crops from countries other than Ukraine can make up for the shortage and bring down and stabilise the world market price for wheat.

2. How does the world grain trade work?

After the harvest, most wheat ends up with a handful of buyers: a list of global traders that has shrunk from a few dozen to four dominant multinationals after mergers in recent decades. These multinationals are collectively referred to as ABCD: ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus. They are not well known because they mainly deal in bulk goods and make products such as fodder, corn syrup, or flour — not exactly something you’d see in eye-catching ad campaigns. However, these companies are powerful. Cargill is the seventh largest food giant in the world, after companies such as Nestlé, Pepsi, Coca-Cola, Philip Morris and Unilever.

The four multinationals trade more than 70 percent of the grain and resell it to the highest bidder. They dominate the grain market and can take advantage of price differences that arise between exporting and importing countries. With their large storage, processing, and logistics facilities, they can quickly respond to shortages. It has not been demonstrated whether they also create shortages in order to benefit from rising prices or whether they make price agreements among themselves.

A recent study by Follow The Money provides an insight into the financial parties involved in the grain trade. This study shows that a lot of futures are traded by investors (not traders) who take options on future grain productions. Those options are traded again, which can lead to speculation.

Since, until recently, there was less supply on the world market, the price that ABCD could ask rose. The multinationals are not doing anything illegal under the world trade rules. Grain is treated as a commodity like oil or coal, and they want to secure their own product lines and revenue. They look at the available stock, how much they still have. However, there is also a lot of psychology in trading, just like in the stock market. Prices increased because of the war as well as due to supplier problems caused by COVID-19 and climate change.

3. Who owns the wheat in Ukraine now?

Global wheat brokering is not transparent in all respects. Most wheat is traded with futures: contracts on future production. ABCD work with these futures to secure their future supplies. In all likelihood, this was also the case with the wheat that is still in Ukraine. What happens in times of war? It is plausible that the signed supply contracts are no longer valid due to the ongoing force majeure. In fact, the Ukrainian exporters “defaulted” by not delivering the wheat. However, the force majeure negated the obligation to deliver. The result: the wheat that is still stored in Ukraine is owned by the exporters.

In areas now occupied by the Russian military, Ukrainian wheat is confiscated and shipped to friendly nations such as Syria. Internationally, this is seen as a crime because it involves trafficking stolen goods. Legally this should be considered handling stolen goods.

4. What will happen to the world market price if wheat from Ukraine is exported?

It depends on how much wheat is exported from Ukraine and who owns the wheat. If the wheat is bought and donated to the WFP, this will have little to no effect on the world market price. If this wheat is traded through ABCD, it could significantly lower the price on the world market in the short term. However as the situation in Ukraine is expected to remain unstable for the time being and the ports on the Black Sea cannot be used, food prices are set to quickly rise again once supplies from Ukraine are traded.

5. How long can the grain be stored in Ukraine?

How long the wheat stored in Ukraine can remain fit for human consumption depends heavily on the conditions it is stored in. Under favourable conditions, wheat can be stored for several years. Optimal conditions involve climate control with ventilation and cooling. In principle, the storage facilities in Ukraine are good, but the question is whether air conditioning and fans are on given the high fuel prices and uncertainty about exports. This means that the current value of the stored wheat has not been determined and this may affect the decision of whether or not to store the wheat safely at the associated costs. It is also unclear whether the infrastructure needed to guarantee proper storage is still in place everywhere.

Another dilemma is that the winter wheat harvest is imminent in Ukraine. This requires the current storage capacity to be freed up, but that is not the case.

6. Have other countries already increased their weight production?

To secure wheat (primarily) and other foodstuffs for their domestic markets, lots of other countries are imposing restrictions on exports. As far as we know, 50 countries have now taken this kind of measure for various food crops. These measures further push up the world market price for wheat, but also for other grains such as rice.

After war broke out in Ukraine, India’s Prime Minister, Narendi Modi, announced that India was going to make up for the shortage of wheat on the world market from their national food reserves. India is one of the few countries in the world where the government is a major buyer of food. They use this to build up reserves that are made available to the poorest in times of food shortages. This policy costs the government about 10 billion USD a year, but it has reduced absolute malnutrition in India. Unfortunately, shortly after Prime Minister Modi's announcement, there was an extreme drought that threatens the coming harvests. Because of this, India did not follow through on Prime Minister Modi’s announcement. The country kept the wheat reserves available for domestic use.

In: VOA, 20 April 2022

India is expected to reduce shortages of wheat on global markets created by the war in Ukraine as overflowing warehouses help it step up exports. Although India is the world’s second biggest wheat producer after China, it has been a small exporter, selling wheat mostly to Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and some Middle Eastern markets. But as supplies from Russia and Ukraine are threatened by the war, India is eyeing markets across Africa and Asia. The Black Sea region is one of the world’s important grain-growing regions and the two countries together account for about 30 percent of global exports.

On April 20th 2022 Modi said India had "enough food" for its 1.4 billion people and was "ready to supply food stocks to the world from tomorrow" if the World Trade Organization allowed.

India is relying on surplus stocks in its warehouses as it eyes exports - its vast northern and central plains grow millions of tons of wheat and farmers harvested bumper crops for five straight years until 2021. The country is holding nearly two-and-a-half times the buffer stocks that it needs to maintain. Millions more tons will be added this month as farmers bring their produce into markets following the wheat harvest.

India’s exports have traditionally been low because the government buys huge stocks of wheat from farmers at guaranteed prices – those prices are usually higher than overseas market prices, meaning exports are not competitive. But the huge increase in global prices has changed that, making it lucrative for traders to sell Indian wheat abroad. An increase in exports was already witnessed in the fiscal year that ended in March – India’s wheat exports hit 7.85 million tons compared to 2.1 million tons in the previous year.

Bron: VOA, India Steps Up Wheat Exports Amid Supply Disruptions Due to Ukraine Crisis

7. Why do countries with a high wheat consumption not produce their own wheat?

In the months before the start of the war (February 2022), Egypt imported wheat from Ukraine worth 270 USD per tonne. In May, the average import price was 475 USD per tonne. To prevent social and political unrest, the Egyptian government continues to subsidise the price of bread and keep it low. The costs of that subsidy programme are enormous.

Countries such as Turkey, Egypt, Pakistan, Sudan, and Tunisia are all heavily dependent on wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia. The possibilities for expanding domestic wheat production are limited due to the often short and dry growing seasons. The limited availability of water also plays a role in these countries. Irrigation cultivation in combination with drought-resistant seeds can increase production, but requires quite a bit of investment. If these investments are made, they only contribute to a greater degree of self-reliance in the longer term. As a result, these countries will remain dependent on imports, at least for years to come. Moreover, price fluctuations in the international grain markets will feed through to domestic food prices.

In Africa, countries such as Tanzania, Kenya, and Ethiopia have favourable climate conditions for wheat production. However, production costs in these countries are significantly higher than in Ukraine, which has the advantage of fertile “black” soils, cheap energy, cheap fertilisers, and huge areas with highly mechanised production techniques.

With a few tricks up your sleeve you can produce wheat at farm level in Ukraine for 90 USD/tonne (Kingwell 2016). Transport to the export ports is still about 130 USD/tonne. This means that a tonne of wheat for export from Ukraine could be sold for 220 USD/tonne in recent years.

Tanzania could boost domestic wheat production by subsidising fertiliser and fuel. Lifting import taxes on, for example, tractors and other mechanised tools needed for large-scale wheat production also helps. It may be necessary to impose import taxes on foreign wheat, which may be problematic due to WTO rules on free trade. Regional treaties to stimulate food trade between countries in East Africa, for example, can further help increase the resilience of food systems. Finally, countries can also reduce dependence on the world market by stimulating the production of food crops other than wheat, such as cassava, corn, sorghum.

In: The Citizen, 23 March 2022

Dar es Salaam. With the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine having adverse effects on global wheat supplies, the government says it is taking measures to address any price surges, or shortages that may result from the conflict. The Minister for Agriculture, Mr Hussein Bashe (pictured), said although the country currently has sufficient supplies, the government has been holding meetings with individual importers to discuss price movements in the market.

The Citizen has learnt that in addition to meeting with importers, the government also plans to involve producers and farmers. “Among the things we have agreed upon is that they should continue to set fair prices. As we continue to monitor global prices, we don’t expect them to inflate prices locally,” Mr Bashe said.

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) shows that Tanzania’s annual domestic wheat consumption is estimated at more than 1 million tonnes per year, while total annual production stands at around 93,184 tonnes. This means that Tanzania imports about 90 percent of the wheat it consumes. “We import an average of 800,000 tonnes annually, and while some is used locally, some is processed and exported to neighbouring countries,” Mr Bashe said. He added that Russia and Ukraine – along with the United States and Canada – were Tanzania’s major sources of wheat. “As a country, we have also initiated efforts to increase wheat production locally in partnership with the private sector. For instance, we have already distributed over 200 tonnes of quality seeds to farmers in the northern regions,” he said.

Apart from ensuring the availability of improved seeds, the minister said the government also plans to propose a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with importers that would ensure they fully supported the initiative to boost local production. “We want them to agree to buy all locally produced wheat, and only import to bridge any deficit because when farmers are assured of a reliable market and stable prices for their produce it stimulates production,” he said.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a member of the Tanzania Grain Millers Association (Tangrama) said the conflict had put them in a precarious situation. As part of remedial measures, he asked the government to review import duty on wheat. “We request for stay of application of CET (common external tariffs) rate on wheat grain to zero.