News

What stops the growth of Siberian wildfires?

In recent years, millions of hectares of forest have burned in northern Siberia. These wildfires led to record-breaking carbon emissions and severe air pollution. A new study has identified the key factors that have limited the growth of these fires. The researchers discovered that both weather conditions and landscape features play crucial roles in stopping fire spread in this area. A shift from hot and dry to cold and wet weather is the main limiting factor for fire propagation. However, with climate change, hot and dry days are expected to become more frequent, which might result in the growth of even larger fires in the future.

A new study by researchers from Wageningen University & Research, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and the University of East Anglia has revealed which climate and landscape factors limit the growth of wildfires in Siberia’s northern forests. The researchers analysed over 27,000 fires, which together burned 80 million hectares of forest between 2012 and 2022. This is the first study to map fire-limiting factors on this large scale and in such spatial and temporal detail. The findings have recently been published in the scientific journal Global Change Biology.

How do wildfires stop?

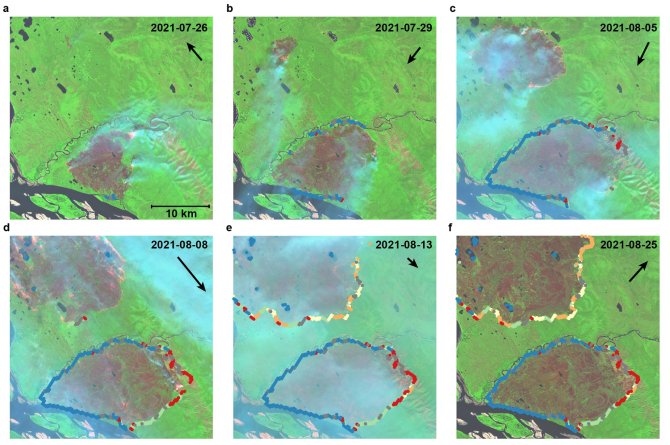

Wildfires in Siberia are rarely suppressed and can burn uncontrollably for many months. They are ultimately stopped by changes in weather conditions or landscape features, such as a transition from hot and dry to cold and wet weather, or the presence of a wide river or a road in the landscape. Researchers Thomas Janssen and Sander Veraverbeke used satellite imagery to analyse 2.2 million locations where fires stopped spreading at some point, to determine which factors limited fire spread at those specific locations. “Understanding what stops fires is just as important as knowing what drives them,” says lead researcher Thomas Janssen. “Our study shows clear variations in the importance of the different drivers that limit fire growth, both in space and time. This is essential for improving fire predictions.”

The study found that in 87% of all locations where a fire stopped, its extinction could be attributed to a statistically significant change in one or more environmental factors, while for the remaining 13% no reason for the fire stopping could be found. Fires were either stopped by a change in landscape characteristics (32%), a weather change (23%), or a combination of both (45%). In southeastern Siberia, human landscape features, such as roads and arable fields, played a significant role in stopping fires, whereas in the remote northern taiga, weather conditions were the primary limiting factor of fire growth. As a result, fires in the remote north may grow even larger in the future as the climate becomes warmer and drier.

Can past fires limit future fire spread?

The last decade was marked by an explosive increase in fire activity in eastern Siberia, but fires cannot continue to expand indefinitely. “At some point, there’s nothing left to burn,” Thomas Janssen explains. Using satellite imagery of past fires, the researchers were able to explicitly link some of the locations where fires stopped due to fuel limitations to recent historical fires. The first signs that historical fires limit the growth of current fires are already visible in the recent fire hotspot of Yakutia in central Siberia. “In this region, we have annually looked back over a seven-year period between 2012 and 2021 and found that the burned land area has quadrupled. As a result, it has become more likely that a fire will extinguish at the edge of an older fire, where there is no more fuel.”

Implications for fire modelling and management

The method developed in this study can also be applied to other regions and provide a framework for future global wildfire research. The findings have important implications for improving global climate models and local wildfire models. This can help policymakers and fire management agencies to better predict and respond to extreme wildfires in the future. “These insights are crucial for fire management,” Sander Veraverbeke adds. “If we have a better understanding of how and why fires stop, we can develop more effective strategies to control them and limit their impacts on public safety, climate, and air quality.”

This study was supported by a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council, as part of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.