African swine fever (ASF)

African swine fever (ASF) is an infectious viral disease in domestic pigs and other pig-like animals such as wild boar. The disease can result in up to 100% fatalities in a population. The virus is not dangerous for humans. Wageningen Bioveterinary Research (WBVR) conducts research into this disease.

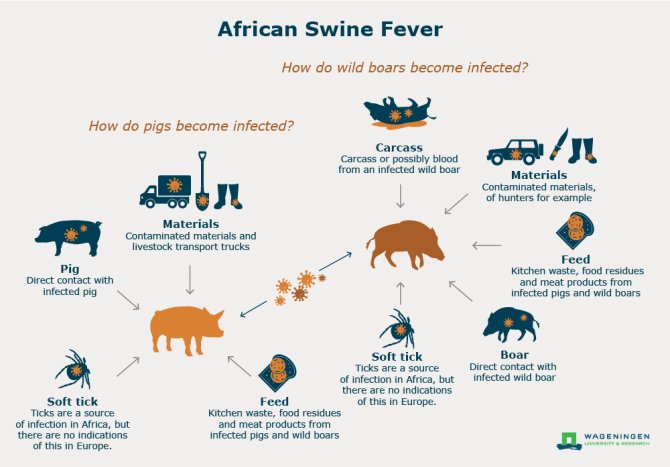

Infection can occur through direct contact between pigs or boars, but also, for example, through soft ticks in (sub)tropical regions, through contaminated materials or contaminated feed. No vaccine is available against it. Since 2014, the disease has occurred in several EU countries. The Netherlands is still ASF free.

To control African swine fever, rapid detection is essential. The clinical symptoms can look very much like those of classical swine fever: fever, weak pigs, lack of appetite, inflamed eye mucous membranes, red skin, (bloody) diarrhea and vomiting. There is no vaccine available for African swine fever.

Tips to prevent spread are:

- Are you visiting areas with ASF infections? Do not take any pig products back to other countries.

- Do not throw pig products away on the street, in nature, or in open garbage cans where wild boar can reach them.

- Do not feed pigs with food scraps, for example when visiting a petting zoo or free range pig farm.

African swine fever infection

The African swine fever (ASF) virus is the sole member of the Asfarviridae family. The disease was first described in 1921, in Africa.

It is the only DNA virus known that is able to infect arthropods (certain soft-bodied ticks of the genus Ornithodoros), as well as mammals. The natural hosts for the virus are suids. This historically refers in particular to warthogs (Phacochoerus spp.), but also for example to bushpigs (Potamochoerus spp.) and to the giant forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni), all of which are endemic to Africa. Domestic pigs and the wild boar (Sus scrofa) are also susceptible to this virus. Soft-bodied ticks of the Ornithodoros genus can also become infected. These ticks occur only in tropical and subtropical regions. For example, in Europe only around the Mediterranean Sea.

The virus is able to survive for several days in the environment. However, this may be extended in the presence of protein (blood, meat) to weeks or months, and even a year. For example, the virus can remain infectious in dried hams (Serrano and similar) for up to 4-5 months. This may even rise to years in frozen meat. The virus can be rendered inactive by heat treatment (at least 20 minutes at >60 °C, 70 minutes at >56 °C), pH <3.9 of >11.5 and responds well to most disinfectants.

Clinical signs African swine fever

The incubation period for African swine fever varies between 2 and 10 days, depending on the virulence of the virus. Clinical symptoms may look very much like those of classical swine fever. Clinical symptoms may look very much like those of classical swine fever: fever, listless pigs, lack of appetite, red skin, (bloody) diarrhoea, vomiting. Bleeding, cyanosis (blue skin) and necrosis of parts of the skin (blackening) may occur. Sows may abort upon infection. Pigs may suddenly die without symptoms being observed beforehand.

Mortality rate

Domestic pigs soon suffer serious symptoms, with a high percentage mortality of up to 100%. However, there are strains of the virus that result in a lower mortality rate, but usually still between 30 and 70%. Pigs surviving the acute phase may apparently recover. But they may remain carriers of the virus - for several months. The symptoms may initially disappear, and can return at a later stage.

Spread of African swine fever

Warthogs and wild boar

In Africa, the reservoir of the African swine fever virus is found in the wild. The warthog and the soft-bodied tick (mainly of the species Ornithodoros moubata) maintain the virus cycle there. Soft-bodied ticks feed on infected warthogs, propagate the virus and pass it on to another warthog at their next blood meal. As warthogs and ticks cohabit closely in warthog burrows, this is an efficient method of spreading the virus. Direct mutual contact between warthogs probably plays a more limited or even no role in spreading the virus.

Wild boar, as known in Eurasia, can also become infected with the African swine fever virus. Their role can certainly not be compared to that of the wild African suids. In wild boar, the disease is usually acute, and virtually all infected wild boar die. Over recent years we have seen the virus being found increasingly in wild boar, and it seems that under certain circumstances, the virus can continue to circulate among wild boar over the longer term or even become endemic.

Pigs

Infection can occur via multiple routes:

Direct contact: Infection of pigs and wild boar may occur via direct contact between an infected animal and a susceptible (as yet uninfected) animal. This ensures distribution within an infected pigsty, for example. Contact between wild boars and pigs kept outside is also an example of this.

Contaminated feed (kitchen waste): All outbreaks outside Africa probably started with feeding kitchen waste (swill) from for example ships or planes arriving from Africa. The virus can easily end up in the food chain through the slaughter and processing of infected pigs. This is not unusual, particularly in small-scale pig-keeping, where people keep just one or a couple of pigs. The virus can survive for a long time in products of this kind. When these products are moved, the virus can be spread over large distances, with the result that it is extremely difficult to suppress. Products like dried sausage or salami can for example be a source of infection, if fed to pigs, taken to a pig farm or left in an environment where they can be reached by wild boars. The sources may be tourists, workers/employers or truck drivers on long routes, alternatively hunters carrying trophies or wild boar products.

Wild boar carcasses: Contact with carcasses or remains left from a hunter gutting a wild boar may result in further infections in wild boar. In addition, as stated above, food remains left in the environment can infect wild boar.

Contaminated materials: Contaminated materials, such as tools, boots and also stable bedding may cause infection in pigs. The quantitative risk of the virus ending up in pigs via this route is not entirely clear at present. Livestock transport vehicles in which infected pigs are being moved, also pose a risk.

Surviving pigs and wild boar: Pigs that survive an initial infection become carriers of the virus. They can carry the virus for several months. These pigs are much less infectious than pigs in the disease’s acute phase. Nevertheless, they may have an important role in the epidemiology, because they ensure that the virus can remain latent over the longer term.

Where does ASF occur?

The disease occurs primarily in Africa, more specifically in the countries south of the Sahara. In 1957 the disease first showed up outside of Africa, in Portugal. Since 1960 the disease spread to Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Belgium and the Netherlands. There were also outbreaks in the 1970s in the Caribbean and Brazil. By the mid-1990s, the virus had been eradicated everywhere outside of Africa, with the exception of the Italian island of Sardinia.

In 2007 the virus turned up in Georgia, in the Caucasus region. From there the virus spread to Russia and other countries, reaching the European Union in 2014. In September 2018 the virus made a big leap, ultimately infecting hundreds of wild boar in Belgium. Besides outbreaks in Asia, there are especially many outbreaks in Poland and Romania. In September 2020 the virus was discovered in Germany for the first time.

Map: ASF in Europe

View the map of the EU with the spread of ASF

- Blue: No ASF, but zones with risk of an outbreak

- Pink: ASF in wild boar only

- Red: ASF at pig farms, with or without infected wild boar

Diagnostics African swine fever

The virus may be found in sick animals in the blood, tonsils, lymph nodes, spleen and liver, among other places. Antibodies soon occur in the blood. Laboratory tests are always essential to make a definitive diagnosis. We use the tests below at Wageningen Bioveterinary Research.

PCR on organs or blood

PCR is used to demonstrate the genetic material of the African swine fever virus. It is also a quick test that is able, within a few hours, to provide a decisive answer to whether a pig is infected with the African swine fever virus or not.

Virus isolation (VI) from organs or blood

The African swine fever virus can also be demonstrated with this test. The virus present in the blood or organs first has to be cultured on cells before it can be demonstrated using a colour method. At least five days are needed before virus isolation can provide an outcome. This test is used to confirm a first positive PCR in a region previously free of ASF and to secure virus for more detailed identification and study.

ELISA and IPMA on blood

These tests show the presence of antibodies produced by the pig. These antibodies may often be shown a little over a week following infection. The ELISA is a quick test in which many samples can be investigated at the same time. A negative outcome is known within one or two days. However, a positive result in the ELISA must be followed up with second test, the IPMA, in order to confirm the ELISA result. This test is a bit more laborious than the ELISA, but can also be conducted within one to two days.

Prevention and control of African swine fever

Four crucial steps may be distinguished in prevention and control, all of which are important in order to limit as far as possible the damage resulting from an African swine fever outbreak.

1. Prevent an introduction

Introduction can only be prevented by being careful with infected animals and products from abroad. The significant measures for this are:

- No import of live animals, meat and meat products from regions where African swine fever occurs. Also bear in mind the meat products that are brought in from affected regions by individuals, for example by truck drivers on long routes, commuting foreign workers, hunters hunting abroad and tourists.

- Ban on swill feeding and being alert to exposing pigs and wild boar ‘by accident' to possibly infected food products (a salami sandwich discarded carelessly outdoors or at a petting zoo, or wild boar with access to kitchen waste via refuse bins or refuse heaps). Pig farmers must also be on the alert for visitors bringing food onto their farms.

- Cleaning and disinfection of livestock transports returning from abroad.

- Cleaning and disinfection of materials used when hunting in or in the vicinity of infected areas.

2. Limit further spread

Introduction of the virus will initially always go unnoticed. Presumably there will be a few weeks between the time of introduction and the first diagnosis. During this phase the virus will be able to spread unchecked to other farms. Measures will be needed to limit this as far as possible under all circumstances:

- Restrict the number of contacts between pig farms. This applies primarily to contact between animals, but also to indirect contacts, such as interpersonal contact and to contact via manure, trucks and other materials.

- Ensure that essential contact is rendered safer by (mandatory) hygiene precautions.

3. Trace a possible infection early

In order to control an infectious disease like African swine fever at source, rapid tracing of a new outbreak is essential. Pig farmers bear great responsibility. They see their pigs daily and will be the first to observe suspected symptoms. In this regard, it is essential that the right follow-up steps are taken quickly to confirm the disease in the laboratory or to rule it out.

4. Control an outbreak quickly and efficiently

- Culling animals on infected farms, followed by cleaning and disinfection

- Tracing possible contact farms, followed by quarantine or preventive culling

- Tightening biosecurity measures

- Transport ban on pigs and pork products

- Improving surveillance in the region where the outbreak occurred.

Preventive culling depends on the situation

As the African swine fever virus spreads much less readily via indirect contact than does for instance classical swine fever virus, the extent to which preventive culling may be effective or justified is unclear. Based on circumstantial evidence, preventive culling related to neighbourhood contacts (undetermined contacts within a radius of e.g. 500 or 1000 meters around an infected herd) is likely to be ineffective and therefore difficult to justify. Preventive culling in other situations may depend on the specific circumstances of the actual contact with the infected herd.

Research by Wageningen Bioveterinary Research

In the Netherlands, safeguarding against and combating African swine fever is a task carried out by the government. Laboratory tests are always essential to make a definitive diagnosis. Wageningen Bioveterinary Research conducts this diagnostics.

We also coordinate the monitoring of wild boarsfor ASF. In addition, we carry out research for maintaining and expanding expertise, as well as advise the government and other organisations on ASF.

Besides this, WBVR can test if disinfectants are effective against African swine fever virus.

We exchange knowledge about ASF with the industry and other interested parties, watch this webinar (2018):

- Unfortunately, your cookie settings do not allow videos to be displayed. - check your settings

Publications

Links

- FAO Animal Health Manual - Recognizing African swine fever - A field manual. Elaborate background information.

- OIE technical disease card African swine fever, 2013 - Elaborate information on the different aspects of the disease.

- Map with the spread of African swine fever from 2007 - June 2019

- DEFRA Preliminary outbreak assessments - Risk analysis by the British government of outbreaks of animal diseases abroad.

- African swine fever - European Reference Laboratory - General information about African swine fever.

- Promed - For fast notifications of animal diseases, with the latest news on animal diseases worldwide.

- Animal Health regulatory committee presentations - Presentations of EU-countries on the current situation of animal diseases.

- Video: How to stay one step ahead of African swine fever (EFSA)

- Video: Prevention of African swine fever in Europe (European Commission)