Longread

We mustn’t ignore the time bomb of climate change and conflict in Africa

People in Africa’s Sahel region are increasingly struggling with the impacts of climate change. There’s an urgent need for agriculture there to adapt to hotter and drier conditions in order to be able to feed a growing population. But conflicts in the region are preventing that from happening. National research institutes in Africa – working in partnership with the Sahel platform run by Wageningen University & Research – say that now is precisely the time to invest in the region.

Government leaders are gathering in Dubai this week for the 28th climate conference. There will be a lot of talk at this COP28 about mitigation: combating greenhouse gas emissions to prevent climate change. But adaptation will also be on the agenda. The idea behind the planned loss and damage fund is to compensate poorer countries for the problems caused by global warming. This is important, but according to Han van Dijk, climate change adaptation is what’s really crucial in many parts of Africa. Van Dijk is a professor holding a personal chair in development sociology at Wageningen University, co-founder of the Sahel platform, and has years of experience in conducting research in West Africa.

“Climate change is already having major consequences for Africa. And in future, heat and drought are going to increase to such an extent that in many places current agricultural practices won’t produce enough food. Meanwhile, there’s a lot of political unrest in the Sahel, the region just south of the Sahara. As a result of those conflicts, not enough is being done to adapt to climate change. I’m really concerned about it.”

If you started in Senegal on the Atlantic west coast of Africa and travelled east in a straight line, you’d pass through some pretty dangerous countries. Coups have taken place in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger over the past few years, and military regimes are now in charge. Chad and Sudan have been unsafe for even longer, with ongoing wars. In the past year, Ethiopia has also seen the outbreak of another major conflict. Somalia has been unstable for 30 years now. The backdrop to this is the rise of jihadism in the region – more on that later.

Migration

The conflicts have direct consequences: people are forced to flee, and they mostly move from the north to regions and cities in the south. “In the 1990s I did a lot of research with the Fulani herdsmen in central Mali, and they’ve now fled, having been persecuted by the government and other population groups. Some live on the rubbish dump in Bamako,” says Van Dijk. When they reach the south, these livestock keepers end up on farmland, leading to further conflicts on land use – conflicts that often drag on for years.

These are settings where the ownership of land and resources has long been concentrated in the hands of a few, while the vast majority of farmers have very few resources at their disposal for earning a living, says Van Dijk. “80% of farming households, whether arable farmers or livestock keepers, live below the poverty line, and they can’t invest their way out of poverty.”

Drought and heat, and migration triggered by conflict, are leading to a decline in food production by livestock keepers and arable farmers. This means food shortages are becoming more common.

Jihadism

It robs young people of their hope for the future, says Van Dijk. And that’s what gives ethnic and religious conflicts a foothold in their lives. “Young people with no opportunities are mopped up by the jihadists. They’re given a Kalashnikov and 50 euros a month, and suddenly they’re three times better off than they were before – the firearm becomes a way of life. It’s not right, but it is a logical scenario if you have no clothes to wear and you can’t feed your children. In 2017 I interviewed herdsmen who had a family and a monthly income of 24 euros.”

Islamic extremism has been spreading across the Sahel since the 1990s, often linked with the trafficking of weapons, drugs and people. Large parts of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso are in effect controlled by jihadists. The recent coups have not helped the situation. The government forces have been resolute in their battle against jihadism, and in so doing have actually driven many people into the arms of the jihadists.

Climate change

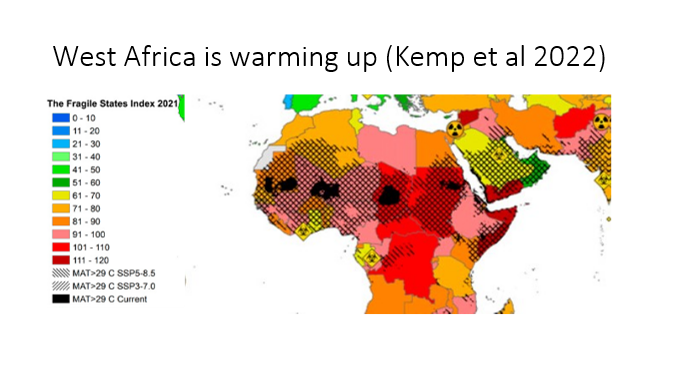

On top of all this, there’s climate change. Many climate scenarios are based on an average temperature rise of 1.5 or 2 degrees. A recent study looked at what would happen under a rise of 3 degrees – a realistic threat. Under that scenario, an area of six million square kilometres would be facing conditions that make food production more difficult. In the figure below, the shaded area will be facing a mean annual temperature of 29 degrees by 2050. This will cause problems for plant growth. Agricultural crops such as sorghum, millet and maize would see a 25% decline in yields.

And that’s just the effects of higher temperatures. The dry parts of the Sahel are also particularly vulnerable to increasingly erratic rainfall patterns resulting from climate change.

This will be exacerbated by the rapid growth in the region’s population. “Nigeria’s population will grow from around 200 million to 400 million by 2050. But also countries such as Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, which currently have around 20 million inhabitants, will be heading to 50 million. And those countries are barely able to feed themselves now. There’s going to be a huge problem there.”

Grievances driven by inequality

The humanitarian crisis is of course reason enough to try and change the situation in this region. But even aside from that, says Van Dijk, it’s conceivable that terrorist organisations or jihadists might come into power there in the future, which then poses a security risk. There’s already a high level of migration at present, a result of conflict and climate change. Research shows that 90% of that migration is within the region. But in future, migrants may be more likely to try to reach Europe. “If the EU continues to keep the door firmly shut, and if we continue to defend our privileges so resolutely, refusing to share in our enormous prosperity, and pushing refugees back to perish in the Mediterranean Sea, I can imagine that at some point the grievances will boil over.”

What needs to be done?

The explosive combination of climate change and conflict in the countries of the Sahel ought to be top of the agenda at the climate conference. “But unfortunately, it isn’t. The topic is being discussed, but mainly by experts from the West, rather than by people who actually live in the Sahel.”

Van Dijk works with researchers who are actually from West Africa and are employed at national research organisations working on agriculture, forestry and livestock, as well as agricultural extension services. These researchers, from Senegal, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, are now calling for a new, integrated approach. “We urgently need large-scale investment in adaptations for the food and agriculture system in these dry regions,” says Van Dijk.

Almost all of the science groups within WUR are organising their research in the region around a special Sahel platform. This platform is working with researchers in West Africa to set up a new institute. They say that now is precisely the time for large-scale investment in climate change adaptation for agriculture. The new institute aims to conduct research and to train young researchers and students.

“In any event, now is not the time to cut spending on development cooperation in West Africa, which is what the VVD and PVV parties want. We know that help isn’t always 100% effective. And yes, some aid money falls into the wrong hands in the context of conflict and weak governments.” But if there are failures in development cooperation, we should aim to do better rather than not do it at all, says Van Dijk. “And we need research for that. We need to know what does work.”

Because doing nothing is not an option. There are already high levels of undernutrition among children in the region, and we can’t afford to see jihadism grow further. “In the 1990s, the minister in charge at the time, Eveline Herfkens, decided not to give aid to poorly run countries. Those were the weakest states. All of those countries then became the source of many refugees. I’m not sure that’s what we want.”

Integrated approach

The integrated approach to climate change adaptation favoured by the local researchers means there will be closer scrutiny of governance, says Van Dijk. “Our partners can see that there’s no shortage of technology, but what’s missing is a good plan for rolling it out.” Such a plan would include a strong farmers’ organisation, fair allocation of land rights and universal access to the technology.

Take, for example, efforts to combat desertification. The UN organisation working on this introduced drip irrigation using plastic hoses. “But those are expensive and many people can’t afford them. They also need to be replaced after five years, and then you’re left with a lot of rubbish. It would be preferable to try and come up with technology that’s better adapted.” The same applies to seed breeders, for example. “From the very start, researchers also need to take into account the context of poverty and conflict. Who will use the seeds? And will they also be suitable for people on the move?”

This calls for interdisciplinary research, with technologists collaborating with social scientists. Van Dijk hopes this is what the new research institute will achieve. It will also be a place where students and researchers of the future can be trained. “The local researchers are taking the lead. As WUR researchers, we’re just providing support and training.” The launch of the new institute will be supported by the Sahel platform for its day-to-day work, and financially supported by Wageningen University’s Global Sustainability Programme.