Longread

Getting Wageningen’s models and modellers to talk to each other

Imagine a simple linear model to explain the relationship between two variables. Or a complex software-based mathematical framework to identify interactions between the climate and our living environment. Those are just two examples of scientific models that can help explain the world as it is today, as well as predict what it will be like in the future. Models like these can support predictions and decision-making based on solid scientific knowledge.

Wageningen’s scientists are world-renowned for their solid, high-quality research. This research is the foundation for the models we are using to accelerate the transition to a circular and climate-neutral society. But the tricky thing about scientific models is that they are often developed individually, based on different kinds of software, and some are more detailed than others. They also draw on different types of expertise. An economic model is not the same as a technological or ecological model.

Certain models might deal with the same topic, but their perspective or scope can be different. Some models might also be based on a different scale. These differences make it difficult to share data and to link models together. They don’t speak the same language or they may simply be outdated and forgotten – and therefore lost. And this leads to missed opportunities, because all that knowledge might be out there, but it isn’t being joined up. Meanwhile, what we really need is comprehensive solutions.

- Unfortunately, your cookie settings do not allow videos to be displayed. - check your settings

Wageningen Modelling Group and MAST

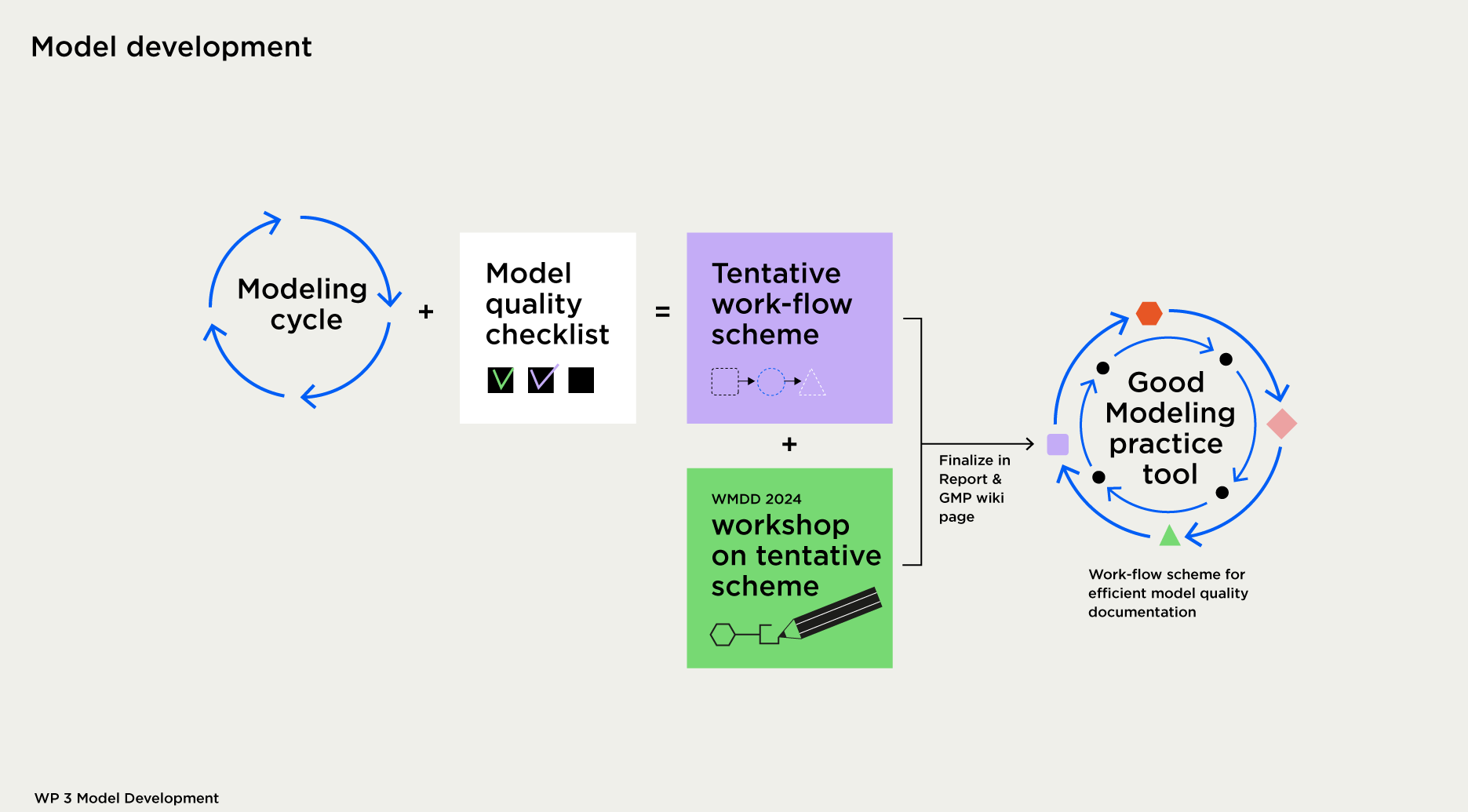

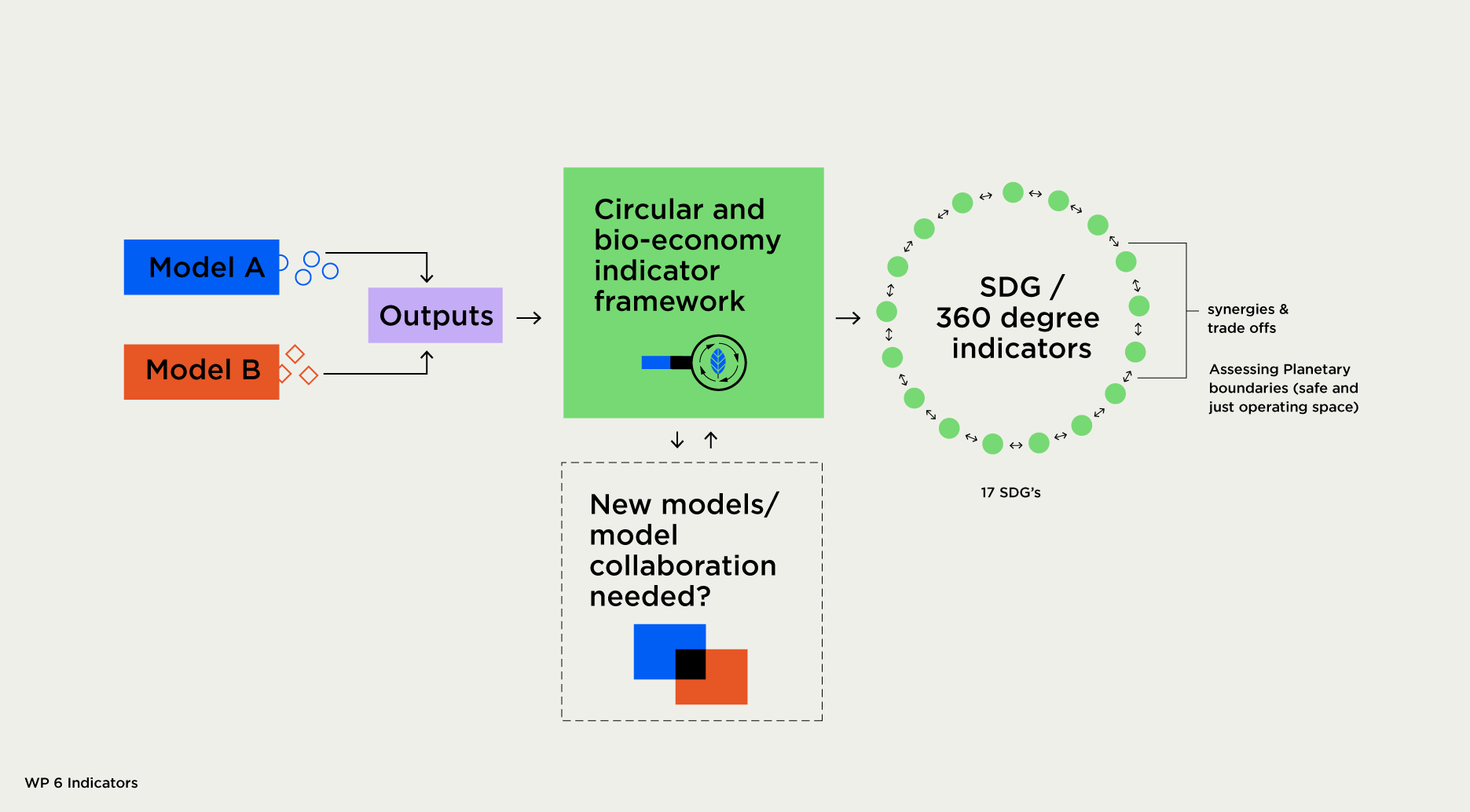

We are working on solutions to these problems as part of our KB project Modelling Assessment of Synergies and Trade-offs (MAST) and in partnership with the Wageningen Modelling Group. We are developing high-quality models, making them visible and accessible, improving and maintaining them and ensuring that they can be put to use. By collaborating on a variety of methodological issues, we aim to learn how best to get models and modellers to work together to apply quality criteria to the development of models (see Figure 1). We anticipate that this will generate relevant and reliable insights for ourselves and our partners. Using models in this way can help us make progress towards a circular and climate-neutral society, for example. Our models calculate the consequences of different choices in the scenarios we come up with.

How did we approach this? First of all, we used quality assessment criteria during the development phase. That included making available the metadata contained in the models in the Wageningen Modelling Gallery. The metadata give us information about a model’s scope, author(s), versions, and current points of contact, for example. They also include information on any available sensitivity analyses, relevant publications and required data, and where those would be located. Data exchange between models can be achieved in a number of different ways, and these may differ for each model and its scope (Figure 2).

We also established the basic requirements for enabling models to work together, and the kind of compliance needed to justify investments and to reduce the risks associated with the use of Wageningen’s models. Our main objective here was to learn from each other and to collaboratively build on existing Wageningen knowledge and experience.

Translation to research in practice

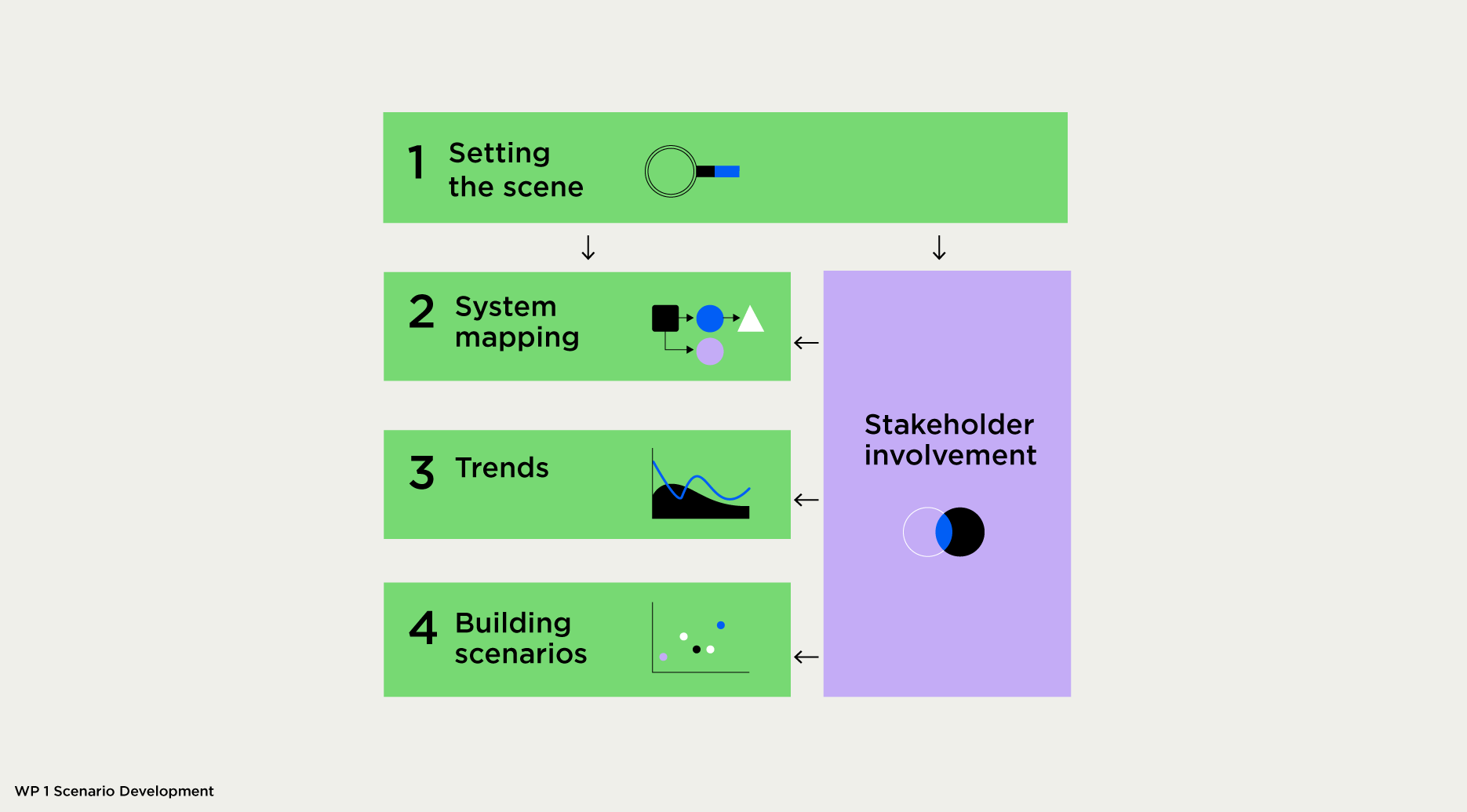

How does that translate to research in practice? Suppose you want to predict how policy measures could contribute to reducing waste and emissions in the garment industry. The first step would be to make assumptions based on scenarios. For example: what would happen if policies were left unchanged and the use of materials also remained as it is now, and what are the possible or desirable scenarios for new policies around the usage requirements for those materials, for example (Figure 3)? You then use models to analyse those scenarios. You can use models in the garment industry to calculate material flows and the effect of any changes in production and processing on the CO2 footprint, based on different scenarios.

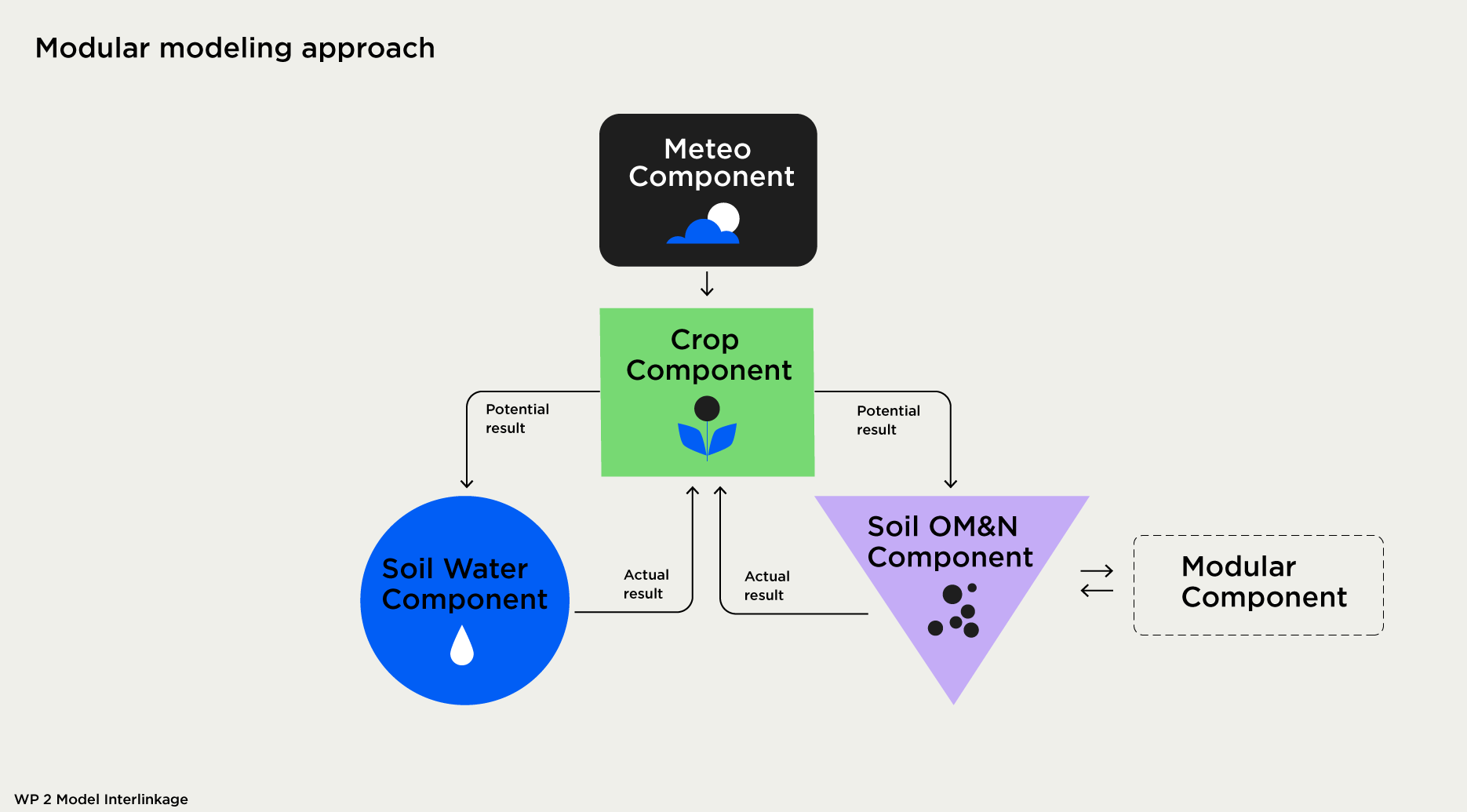

Another example is the transition to healthy and sustainable food production, which involves the interplay of a wide variety of factors. You can use different modules and models to calculate discrete effects (Figure 4).

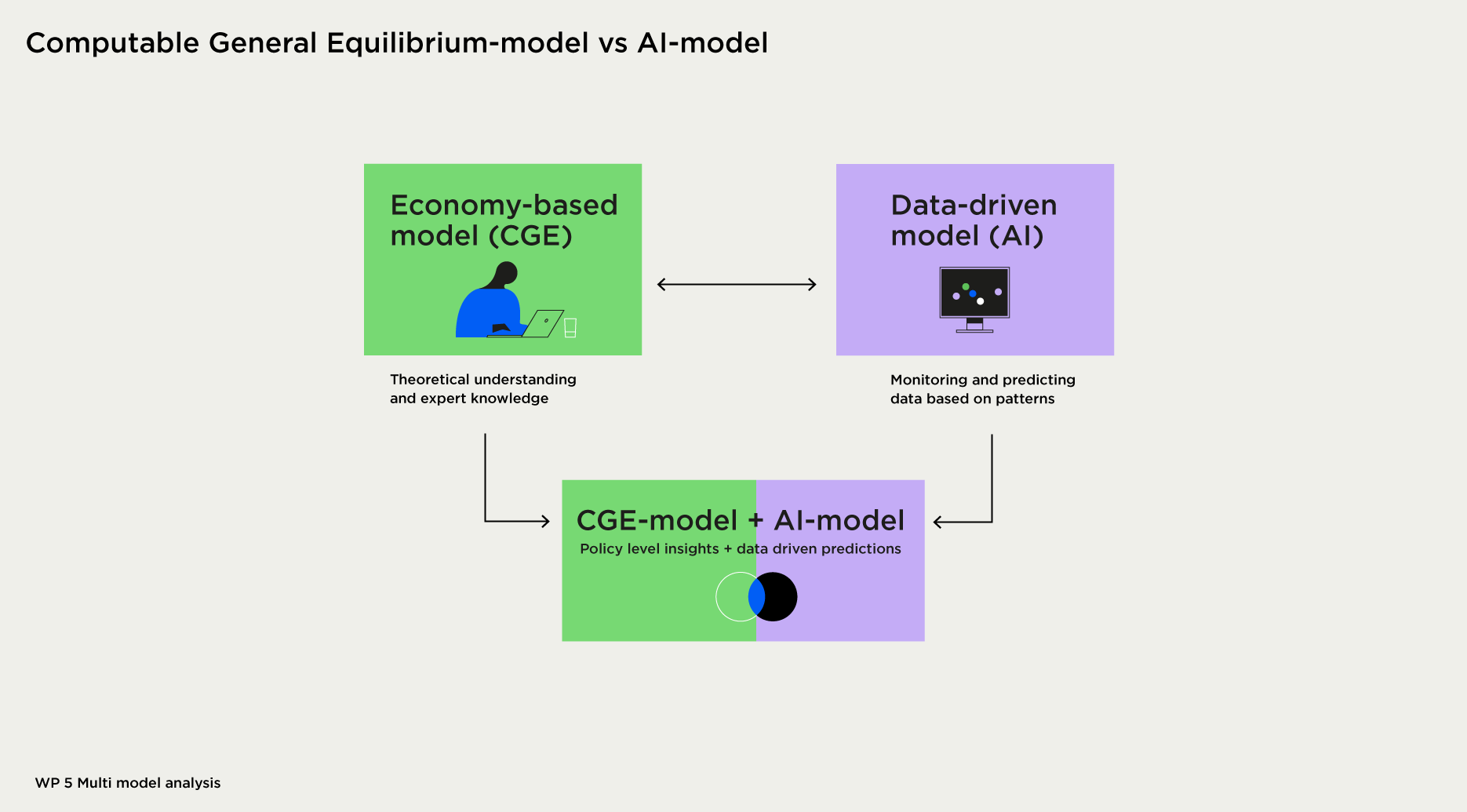

We also explored the possibility of hybrid modelling, using an economic model and artificial intelligence (AI). This maximises the advantages of two types of models. One: simulating a theoretical understanding of economics and trade based on expert knowledge. And two: making trend predictions based on historical data patterns (Figure 5).

Now suppose we can integrate those models. Take, for example, a simulation model that calculates the quantity of raw materials that a particular region could produce under a healthy and sustainable system. Integrate this with a model that calculates how many crops you could then grow, either locally or further afield. Add to this several simulation models for crop growth. And finally, integrate a simulation model that maps soil dynamics with water and nutrient flows. By tying those models together, you can analyse crop performance at the scale of individual fields. Then you can use a variety of indicators (SDGs or KPIs; Figure 6) to scale them up to the level of sustainable diets and food systems for that region.

The models available to us at Wageningen enable us to quantify all sorts of economic indicators collected within a particular project. This might reveal, for example, that extensification of agriculture leads to lower greenhouse gas emissions, but possibly also to costs and risks associated with reduced food security in certain parts of the world. Or that the cultivation of catch crops between agricultural crops results in fewer nutrients being discharged through ground and surface water and being made available to marine food production.

Good Modelling Practice Wiki

The Good Modelling Practice Wiki outlines different ways of getting models to work with each other, and what we learned from doing this. You could see it as a step-by-step guide to the modelling process. The Wiki provides examples of how to blend the outcomes of one model into the outcomes of another and vice versa. But we also explain, for example, how models can work together to answer new research questions, how to maintain the quality of your model and how to properly store that knowledge so that others can reuse it.

Integrated and high-quality research model

Getting models to talk to each other is a new and challenging area of work. We are doing this by focusing entirely on how we model rather than what we model. The lessons learned along the way will benefit other modellers and researchers. They will be able to provide their clients with integrated and high-quality research models, working with colleagues who know how to do this and how to interpret the outcomes of these models. At the same time, we need to bear in mind that using models that can work with each other is not enough on its own. It is particularly important that modellers are open to collaboration. Collaboration means breaking down boundaries in science, not just between models but also between ourselves. More than anything, it means talking. Lots of talking, based on shared basic principles and on the experiences of our co-workers.