Longread

‘We can only stop biodiversity loss if we all work together right now’

Earth Day is a perfect moment to spotlight the new Wageningen Biodiversity Initiative through an interview with the driving force behind this collaboration, Professor of Plant Ecology and Nature Conservation Liesje Mommer. ‘If we deploy all the biodiversity knowledge we have at WUR we can make a huge difference.’

Vanishing insects, soil without earthworms, dying coral reefs: biodiversity is clearly on the decline. Two years ago, the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) published an alarming report with a clear message: we must turn the tide before ecosystems collapse. The future of humanity is hanging by a thread.

We are part of nature, although we seem to forget it sometimes

Biodiversity forms the basis for our existence, providing us with food, clean drinking water, climate adaptation, and a buffer against disease. This realisation is the driving force behind the mission that Liesje Mommer, Professor of Plant Ecology and Nature Conservation, has formulated for WUR: to reverse the decreasing biodiversity curve. She wants to connect all WUR initiatives, research studies and researchers working on biodiversity. Her motto: we are better together.

That’s quite a mission: to bring biodiversity loss to a standstill

“It’s true. Biodiversity loss is at least as urgent a problem as climate change, but with climate change at least we know what measures might help. Implementation may be deplorable so far, but there’s a general sense of what the solution is (limit global warming to <1.5 ̊C). With biodiversity loss, this is much less the case. We know that it’s largely caused by human activity, but we don’t really know how to solve it. There’s no quick fix; what we need is a major shift, one that is defined locally for each area. This is why we must bundle all our resources – from sociology to agronomy, and from ecology to technology.

We only have ten to fifteen years left to turn the tide, and we will not make it at the current pace

As researchers, we have a role to play in this process: it will take all of our commitment and creativity to discover new solutions. This is why I get up in the morning. It’s time for action and everyone has to contribute. Not only WUR, but also politicians have to show courage, as does the industry and the financial sector. Farmers must get the help they need to work with biodiversity rather than against it. This is why biodiversity is now a core theme at WUR.”

Where does your enthusiasm come from?

“I’m a plant ecologist and I study interactions between plants, especially underground: among the roots and fungi. I study these interactions mostly in the context of biodiversity experiments, in Wageningen and in Jena, Germany. I developed a molecular method that allows me to determine plant roots and test their interactions. This has time and again led me to the same conclusion: species-rich plant communities perform better on pretty much every ecosystem function: biomass production, carbon sequestration, water retention capacity, and resistance to disease. Together, plants are stronger; together they form winning teams. I was working on this when the IPBES report was published with its alarming message.

As scientists, we have a moral obligation to think of solutions for the problems we face today

That was when I decided: I have to stand up right now. As Wageningen researchers, we are also stronger together. As scientists we have a moral obligation to think of solutions, for example on how to increase biodiversity in our food system or help farmers to do so. The price for a litre of milk or a kilogram of potatoes is so low that farmers are forced to scale up to make a living. Strip tillage with six different crops is much better for biodiversity, but it’s also more complicated for the farmer, who suddenly has to deal with six different crops, six different markets and six times more bureaucracy. We can only address these issues by working together.”

What do we need to do?

“The power of WUR is that we have all the required disciplines in one place: ecologists, soil experts, plant and animal researchers, technologists, economists, behavioural scientists, and transition scientists. Many people who work at WUR are driven by their passion for creating a greener and better world. Besides, WUR is already involved in many practical collaboration projects with stakeholders such as farmers, nature conservation organisations, ministries, provincial governments and the food industry. If we deploy all our knowledge in the field of biodiversity, together with our partners, we can make a huge difference.

I find it essential that the future Prime Minister prioritises ‘biodiversity’. There is no time to lose!

One of our tasks is to provide politicians with guidelines to shape the needed transitions. I find it essential that the new Prime Minister prioritises ‘biodiversity’. There is no time to lose.

The Wageningen Biodiversity Initiative has three main focus areas. The first is biodiversity in the food system. How can we increase biodiversity in this area? How can we grow more diverse crops and varieties? What challenges and dilemmas does this bring? How can we switch to revenue models where biodiversity plays an integral role? Biodiversity is the base of our food chain, and it is high time to invest in broadening this base.

The second theme is Human Wildlife Interactions (HWI), which includes among other things zoonoses. Pathogens jump more easily from animals to humans because we destroy these animals’ natural habitats and live closer and closer together. However, HWI also addresses how to effectively protect species like the rhinoceros. Once again, multidisciplinarity is crucial in this context. For example, ecologists focus on structuring better habitats. Sociologists show that conflicts between humans and animals are a consequence of conflicts among humans. Look at the reintroduction of the wolf in the Netherlands. That is not a wolf-human conflict, but the result of the non-matching visions of nature conservationists and sheep farmers. The challenge is to colour in the picture together, instead of erasing each other.

The third theme is concerned with the value of nature. You can interpret this as the economic value that nature offers us – clean drinking water, fertile soil, income from tourism – but also as the value that nature inherently has. Who determines this? And how much space does nature need? So biodiversity is not only about species diversity but also about justice. Is it fair that humans get to decide everything for all other living beings on this planet?”

Photo: Liesje Mommer (by Guy Ackermans)

Why is biodiversity loss a problem for humans?

“There are many animal species whose role in the ecosystem we do not fully understand until they disappear. Biodiversity is therefore also a kind of ‘insurance’ against unknown changes in the future. The ecosystem functions best when it is diverse; it makes it more resilient. The loss of a single species can be compensated for, but if multiple species disappear, the system may collapse. Biodiversity is seen as a buffer against disruptions such as climate change: drought and floods. For example, when one of our German research meadows was flooded, we discovered that plots with different kinds of plants recovered more quickly than those with a single plant species.

Biodiversity is also seen as a buffer against diseases. The American scientific journal PNAS recently reported that ‘biodiversity restoration’ is key in preventing zoonoses.

The world currently contains more human-produced material than natural biomass. That’s really shocking to me.

Biodiversity is therefore useful for humans, but it also has intrinsic value. Who are we to decide that a hoverfly has no value? Humans have transformed 80% of all landscape on Earth. There is no more real wilderness left – not even on the North Pole or in deep oceanic troughs. The world currently contains more human-produced material than natural biomass. That’s really shocking to me.”

Can we still turn the tide?

“Yes, but we have to start right now. We only have ten to fifteen years left to turn the tide, and we will not make it at the current pace. What we need is large-scale action to protect biodiversity and a global transition to sustainable production and consumption patterns. For example, it essential that we reduce our meat consumption, and that we develop agricultural methods that allow farmers to work with nature, rather than against it.

We only have ten to fifteen years left to turn the tide, and we will not make it at the current pace

We have to make it easier for consumers to make ‘biodiverse’ choices. Researchers can help governments to provide the right incentives and behavioural scientists can help nudge people in the right direction. Setting an example also works really well: a farmer who already does strip tilling with good results is more likely to arouse his neighbour’s curiosity.”

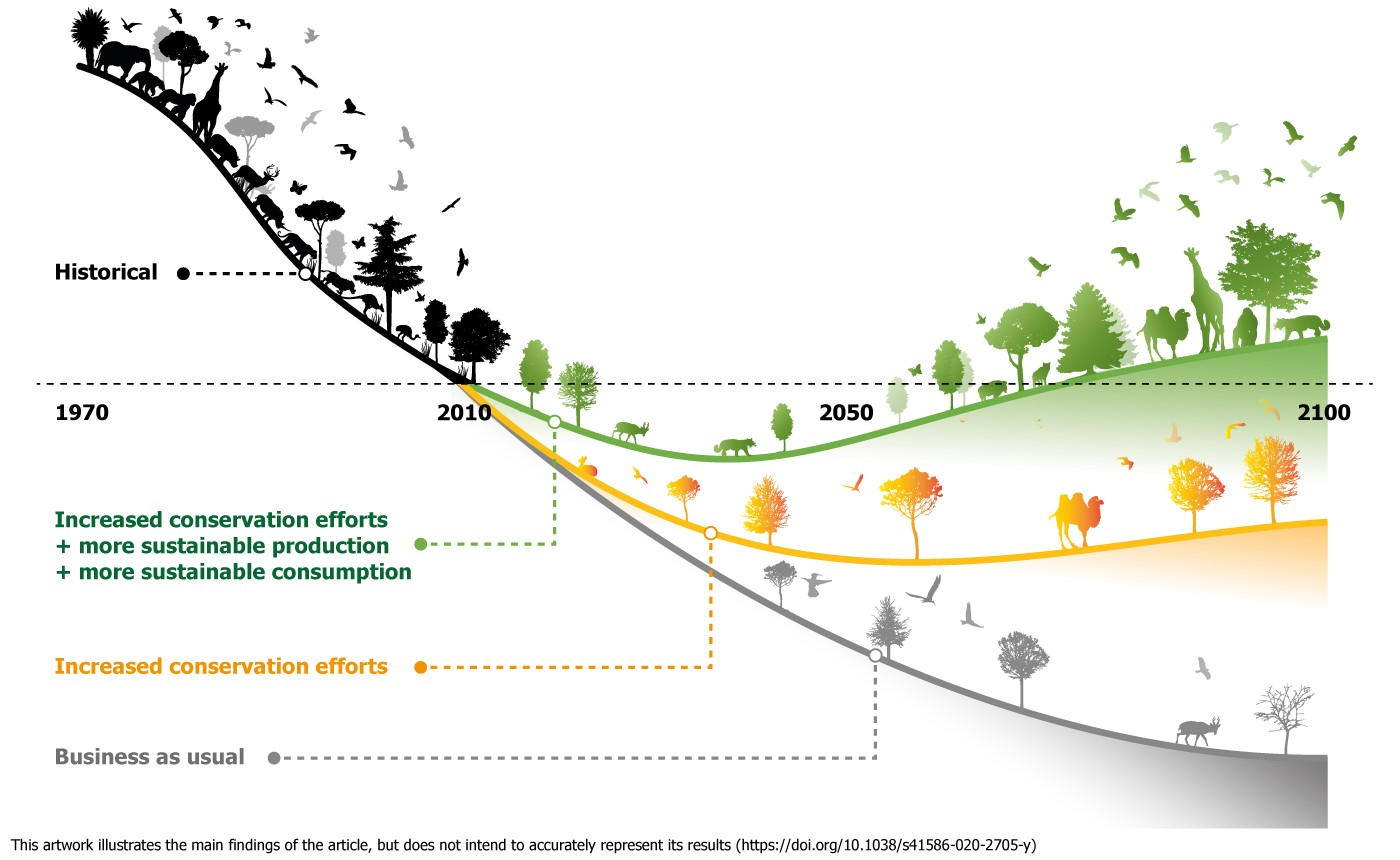

Biodiversity loss curve

Black: The historical biodiversity loss curve before 2010

Green: with effort through more sustainable production and consumption

Orange: without more sustainable production and consumption

Grey: if we continue on our current path

This infographic was published in Nature magazine: Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy

Working to save biodiversity: the Wageningen approach

Is there a specific animal or plant that makes your heart beat faster?

“Everyone has favourite animals – I personally love squirrels and long-tailed tits, but what’s really important to me is the interconnection and diversity in nature. No green deserts full of English ryegrass, but meadows and ditches with flowers, buzzing with insect life. People living in harmony with nature rather than trying to fight it. We are part of nature, although we seem to forget it sometimes. In my opinion, one of the most important things we need to do is restore people’s relationship with nature.”

Is this relationship disrupted by ignorance? Nearly two-thirds of Dutch people don’t know what biodiversity stands for.

“I think everyday knowledge of nature has largely disappeared because more and more people live in cities, but the COVID-19 pandemic has helped us to once again appreciate the greenery in our surroundings. My own love for nature comes from my childhood. My favourite book was Ronia, the Robber’s Daughter, a story that largely takes place in the Swedish woods. I loved the fact that Ronia lived outdoors, in harmony with nature. How she enjoyed the green of the woods, the power of the river. When I think about it, Ronia was also a connector: she tried to reconcile two rivalling gangs of robbers. This role of connector really appeals to me, ha ha!”

Do you ever get discouraged?

“Yes, of course, but if I’m not hopeful, I cannot do anything. There are at least seven hundred research studies related to biodiversity within WUR, which really gives me hope. And it’s not too late yet. It’s an enormous amount of work, but we have so many incredibly clever and creative people. To quote Nelson Mandela: ‘It always seems impossible until it’s done.’ When I feel down, I remind myself of these words and it gives me courage again. Or I go outside – into nature. After all, that’s what I do it for.”