Interview

Collaborating with Chinese partners: “A strong tie and mutual trust are essential”

Academically collaborating with Chinese partners is extremely interesting as they come from one of the biggest and most influential countries in the world. Yet it also raises questions. In this six-part interview series we are going to discover the nature of that collaboration and how it benefits the partners in both Wageningen and China. Part one: Nico Heerink (65), Professor of Development Economics, talks about the importance of mutual trust.

Why do you work with Chinese scientists?

“Because it’s a very interesting country from the perspective of our chair group’s research theme: development economics. After the economic reforms and the ‘open-door’ policies’ (beginning of foreign trade, ed.) in 1979, China developed extremely quickly. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, relatively little was known in the West about these reforms and how they contributed to reducing poverty and sustainably managing natural resources such as land and water. There was hardly any scientific collaboration. When China opened its doors, we – and innumerable scientists around the world – were very curious.”

How did you manage to get a foot in the door?

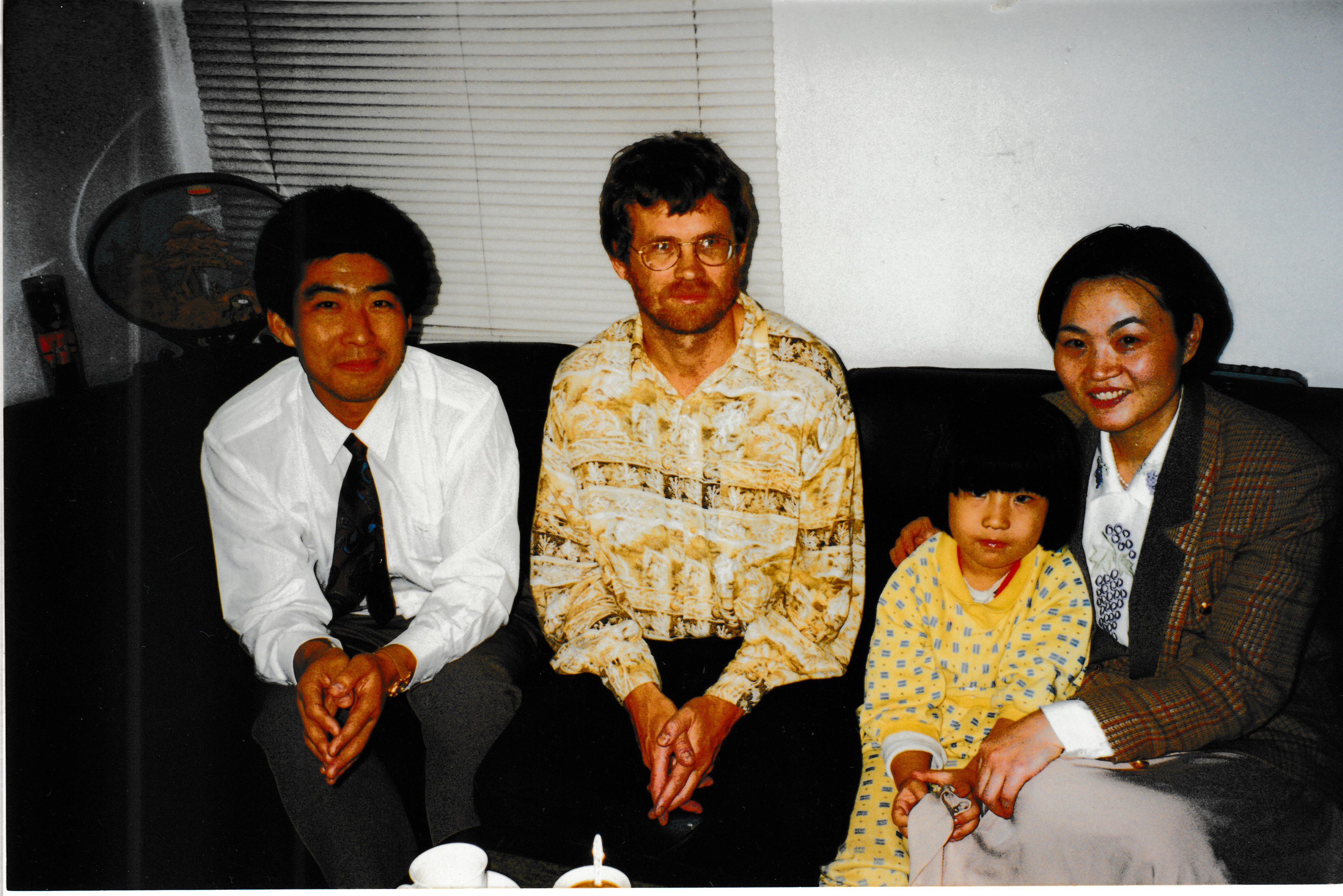

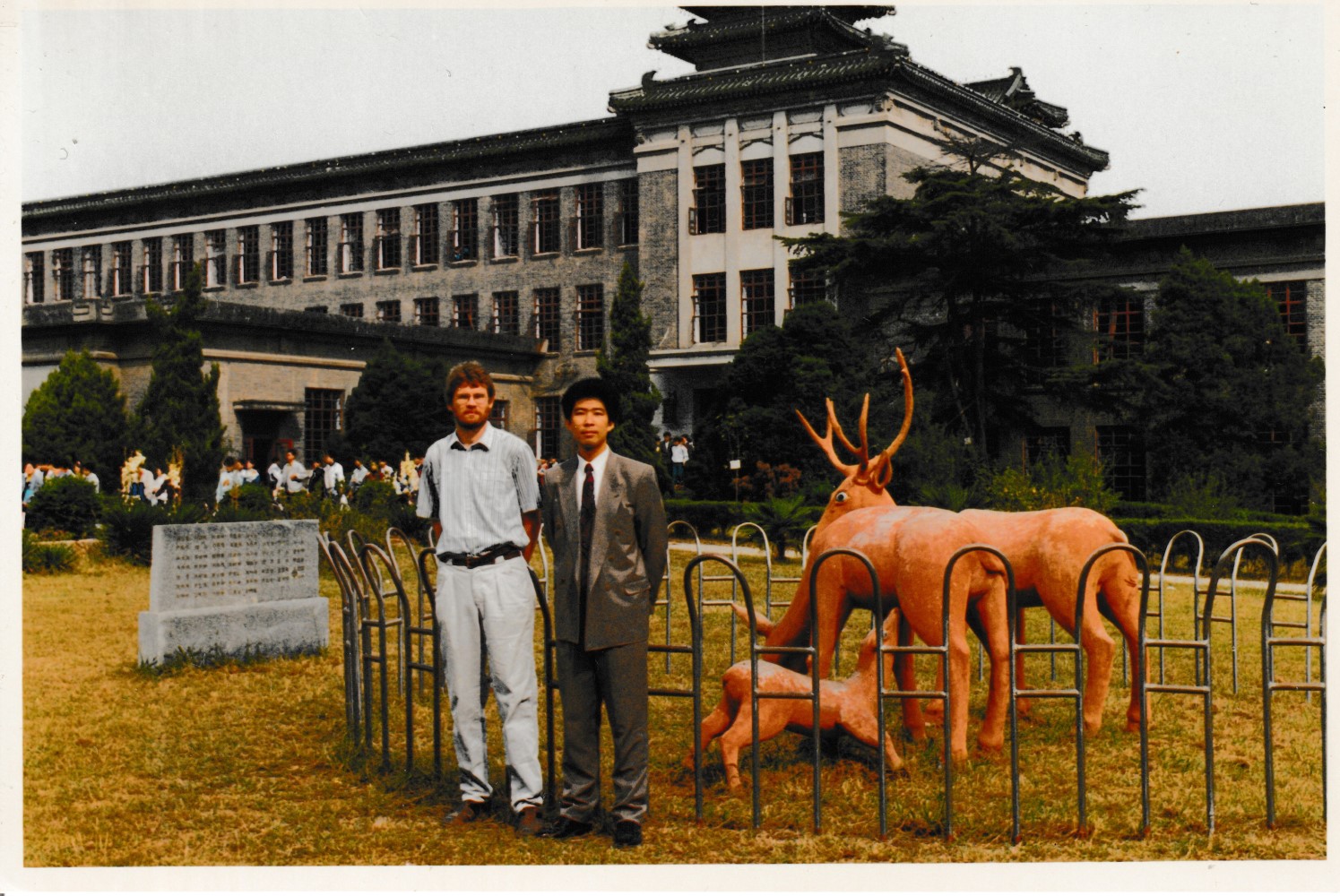

“That was pure coincidence. In 1993 we received a letter from Futian Qu, a young staff member at Nanjing Agricultural University (a thousand kilometres south of Peking, ed.), who asked us if he could come to Wageningen for a year to work on economics of sustainable land use. He had a letter of recommendation from his rector, who emphasised that Qu had a lot to learn about our Western methods of teaching and research. This was the first time that we had welcomed a young Chinese researcher. Prior to that time, our research had mainly focused on Africa.”

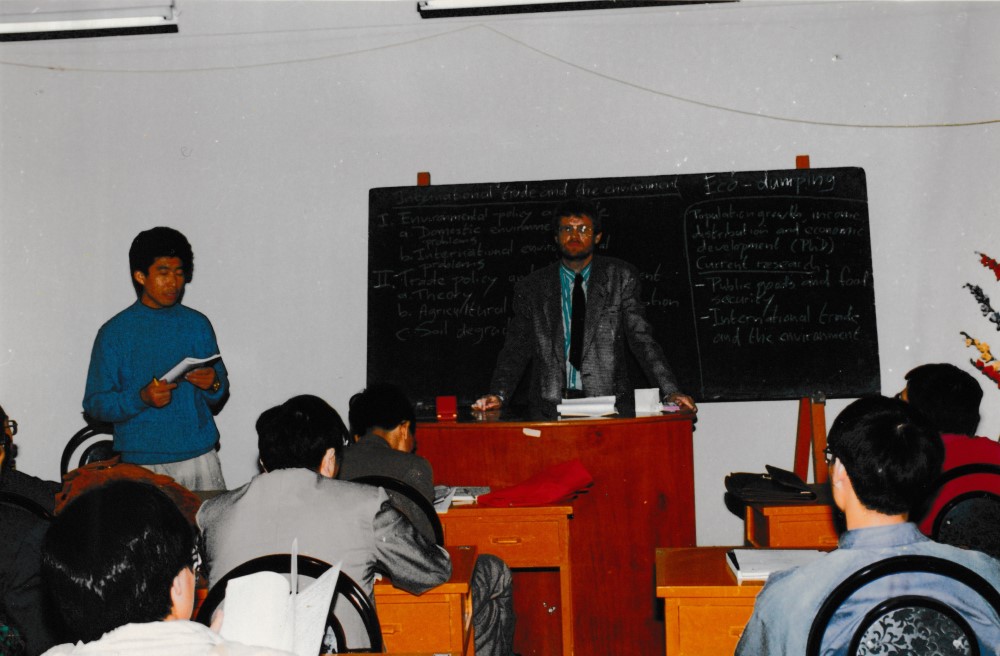

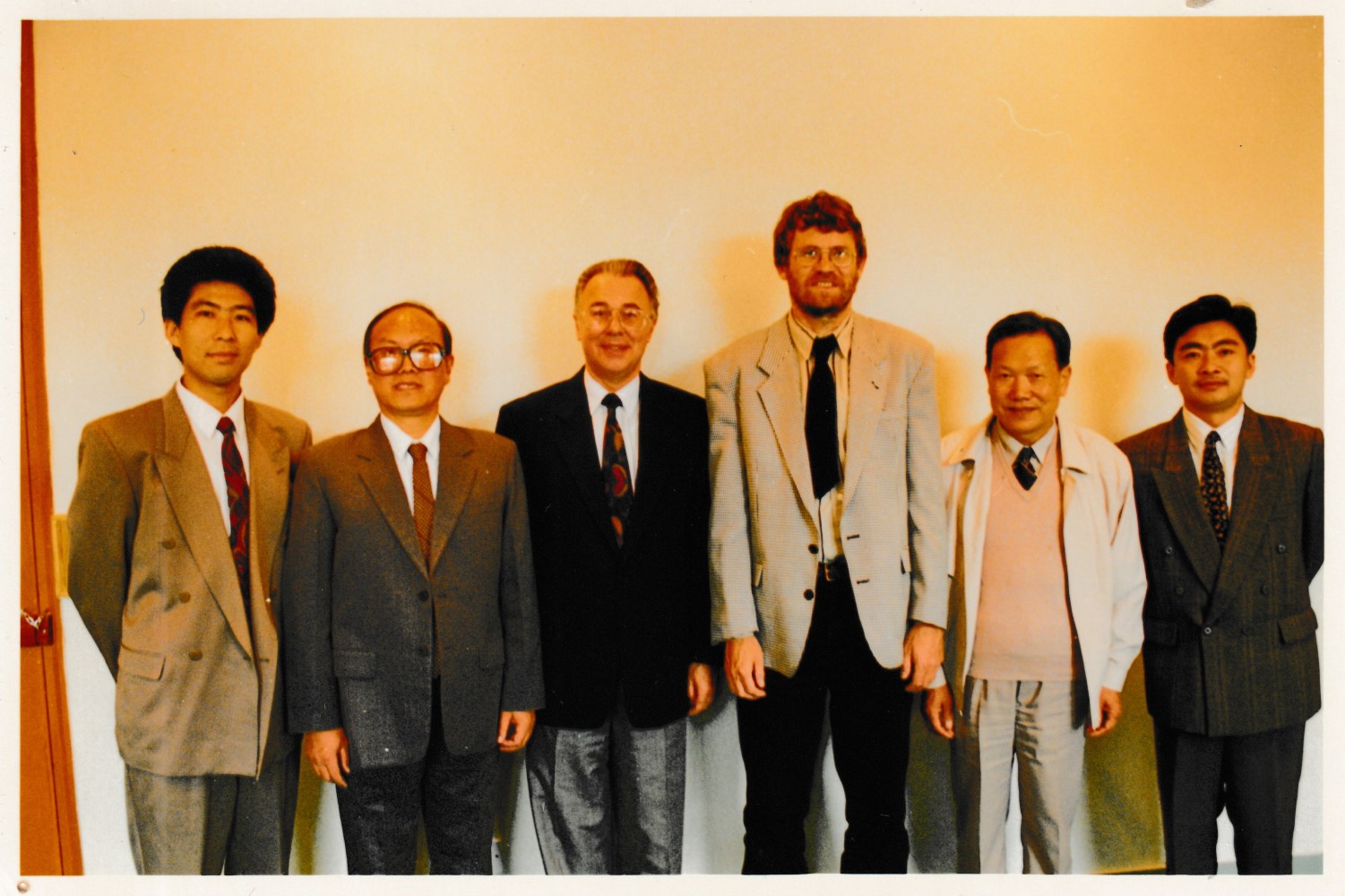

“Qu, Arie Kuyvenhoven – then the chair group holder – and I worked very well together. In October 1995, Arie and I visited Nanjing to make plans for further collaborative ventures. Simultaneously, funding agencies such as the KNAW, NWO and the EU displayed increasing interest in working with parties in China. As a result, since 1997 we’ve conducted various large, joint teaching and research projects with the College of Land Management (part of the university, ed.) in Nanjing. In addition, Qu’s career advanced quickly – first at the university and then with various local governments – which provided us more opportunities for expanding our research activities and reaching out to local policy makers.”

Were you distrustful when Qu arrived in 1993? He came from a Communist country.

“No. We realised that we could learn a lot from him and he could learn from us as well. By working together, we hoped to make a useful contribution to sustainable agricultural development and poverty alleviation in rural China. Because Arie and I were able to talk very openly to Qu about all sorts of subjects, also those not connected to our work, we created a lifelong friendship with one another.”

How different is/was Chinese science?

“Futian Qu was one of the first of the younger generation of researchers. The older generation – prior to the ‘open-door’ policy – spoke hardly any English and read very few international publications. Education particularly focused on copying your teacher’s factual knowledge. Many researchers would collect available statistics from the local government rather than going into the field and asking people, for example, about how they used their land. That has changed since then.

Research in China leads to knowledge that we can also apply in our collaboration with other developing countries.

Nevertheless, we here in Wageningen devote a lot of attention to encouraging Chinese PhD students and young visiting staff – about six to eight a year – to think critically and to determine what they themselves want to examine instead of letting it be prescribed by their supervisor.”

We equate science with critical thinking. In that light, are the results of Chinese research reliable?

“Yes, the results of our joint research are certainly reliable. In general, Chinese scientists are very precise and dedicated. In addition, we collaborate mostly with researchers who have received their PhD here and thus received more training in thinking critically. But let’s be honest: there are risks as well. Some Chinese, especially the younger ones, tend to look for those research results that they hope to find. I try to convince them that what’s really interesting are findings that you didn’t expect beforehand, because that can often lead to new insights.”

Are there more risks involved in the collaboration between WUR and its Chinese partners? Ingrid d’Hooghe at the Leiden Asia Centre recently said that the quality of research was being threatened because of China’s increasing refusal to accept scientists who are working on sensitive issues.

“Our work is hardly related to sensitive issues. We don’t examine subjects like freedom of the press, human rights or the situation of minorities.”

Isn’t that naive?

“We try to stay out of current discussions as much as possible, certainly if they’re irrelevant to our own research. For example, Chinese researchers need to obey the formal Chinese territorial boundaries when they show maps of the country in their publications. Some of these borders are disputed by other countries, like the border in the South China Sea.”

We are working together with researchers who have received their PhD here and who are thus trained in critical thinking.

“Because the exact location of those territorial boundaries have nothing to do with the contents of the articles themselves, we avoid drawing boundaries when they are disputed. On the other hand, several years ago we did adjust a proof of an article because Taiwan wasn’t included in the map of China.”

So don’t you go along too much in the political debate about Taiwan?

“The Dutch government recognises the ‘One-China’ principle (there is only one sovereign Chinese state, Taiwan being part of it, ed.) so it isn’t up to us as scientists to take a position on this issue. In the end, what we want is for our research findings on sustainable land use and poverty alleviation in rural areas to find their way without interference from anyone. And that’s been successful; we’ve published a lot in distinguished international journals.”

How do you know for certain that the government has no influence on research results?

“Our contact with the scientists at the College of Land Management in Nanjing goes back 30 years. Because we’ve known Qu for so very long, and four of his colleagues have obtained a PhD with us in Wageningen, we’ve been able to build mutual understanding and a reliable relationship. In addition, our Chinese colleagues are members of advisory bodies at the provincial and national levels, so the findings of our research, including our policy recommendations, find their way to the Chinese government. Hence, it doesn’t only work top-down. Even if we obtain and present less favourable results about, for example, land degradation, water pollution or illegal land transactions in urban expansion, we’re free to publish those and they reach their ways to local policy makers.”

You say that you can move freely in China, but is that really so?

“Not always, for sure. I lived in China from 2004 to 2007. In 2005 when I was visiting a village with a delegation from the World Bank and walked several minutes away from the group, I was immediately followed by someone who stayed about 20 meters behind me. I don’t know who was responsible for that. It could have been a wary village leader. In general, you do notice that the government’s control has become stricter in the past few years. But up to now, we’ve had little trouble with that. Our advantage is that our Chinese colleagues can explain to local governments and village leaders the importance of a scientific approach, based on for example random selection of households to be interviewed. So we’ve always had much freedom of movement in our field research and in choosing whom we speak to. Village leaders sometimes want to decide that for us, to make sure that they leave a good impression, but we’ve always been able to prevent that.”

So independent research in China depends on good contacts. Do you also work with other universities?

“Definitely. From 2012 to 2016 I was a visiting professor at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou and I’ve also worked with Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University in Yangling, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and China Agricultural University in Beijing. But our historical tie to the College in Nanjing is so strong that that collaboration is the most rewarding.”

How does WUR actually benefit from this?

“China is now officially a ‘higher middle income’ developing country, whereas in the early 1980s almost the entire population lived below the poverty level. We’ve been able to closely watch and study that process. The contribution from Nanjing has proved crucial: they have much knowledge about national and local policies and the ongoing discussions and they can access Chinese literature and data sets. Moreover, they carry out the field research. All in all, this collaboration has given us important new knowledge about development and poverty alleviation in rural areas. We can apply these lessons when collaborating with developing countries in other parts of the world, such as Africa.”

What lessons exactly?

“We know from China how important it is that all families have their own piece of land, no matter how small, for their own food consumption and as something they can fall back on if they lose an off-farm job. In addition, China has taught us how essential it is to develop a ‘non-agricultural sector’ in rural areas that produces agricultural machines and construction material, processes agricultural output, and so on. This contributes to the further growth of the agricultural sector and creates new employment opportunities.

Lesson to students: never write ‘the Chinese government should

Widespread public investments in rural infrastructure have in turn contributed to further growth in and outside of agriculture. We’ve also learned from China how important it is to first test new policy on a small scale with pilot projects before implementing it on a larger scale. Such a pragmatic approach is a better way of adjusting policy in developing countries than introducing drastic reforms based on Western economic theories, as happened in the 1980s and 1990s in Africa, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Those drastic reforms caused agricultural stagnation and greater poverty in rural areas in almost all those countries.”

You just said that the Chinese government’s control is becoming stricter. Do you notice that at the academic level as well?

“In a certain sense. Most of our Chinese colleagues are members of the Communist Party, and Chinese universities are expected to introduce the government’s ideas. But I don’t consider that to be a reason to exclude Chinese partners from scientific collaboration, given all of the benefits that both sides gain from collaborating. Of course, we adhere to WUR’s code of integrity.”

“In the past few years, an increasing number of people have been saying that the Chinese government is flawed and that its policies must change. That pedantic attitude is fruitless. After nearly 30 years of experience, I know that the tone of the message is crucial, and that's also what I try to teach my students and PhD researchers in Wageningen. When making policy recommendations, you should never say ‘the government should’ but rather ‘the government could consider’. Their autonomy remains intact even though you bring the same message.”