News

Plant-parasitic nematodes on the rise: WUR launches major research project

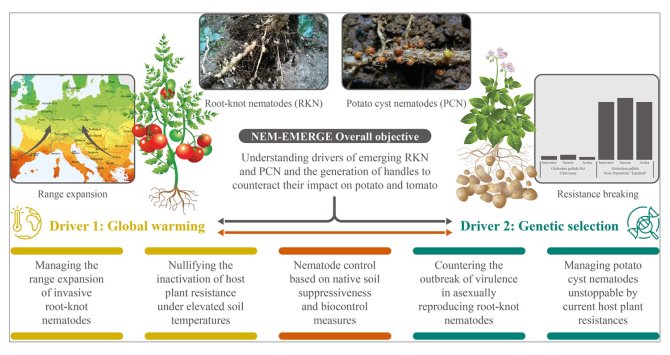

Climate change and genetic selection have brought root-knot nematodes further north in Europe and made cyst nematodes more difficult to control. These emerging parasites threaten major crops such as tomato and potato. To get a clear picture of the proliferation of novel nematode species and populations and to find appropriate and sustainable solutions to these problems, WUR is launching a major research and innovation project with seventeen European partners called NEM-EMERGE. The project has been accepted as a Horizon Europe Project, resulting in 7 million euros in funding.

Root-knot and cyst nematodes form a grievous threat to tomatoes and potatoes. These nematodes occupy places one and two in the ranking of the most impactful plant-parasitic nematodes . Researcher Hans Helder explains how these nematodes work. ‘They drain energy from the plant, causing a plant condition referred to as 'fatigue'. As a result, the crop barely grows and is severely weakened leading to crop loss and hence economic damage. Annually, root-knot nematodes alone cause yield losses of several billion euros. Next to crop rotation and resistant varieties, growers currently use broad-spectrum chemicals to control these nematodes which have unwanted negative side-effects on nature and the environment.’

Climate change and genetic selection

Both root-knot nematodes and cyst nematodes are on the rise. According to Helder, climate change is a major cause of this. "Due to global warming, our winters are becoming milder. As a result, ‘tropical’ root-knot nematodes are moving further north. Whereas they used to be found only in North Africa and southern Europe, in recent years they have also been observed in central France and halfway across the Balkans. In addition, climate change is affecting soil temperatures. At temperatures of 28 degrees or higher, some important resistance genes of crops no longer work. This line of defence that protects plants against parasites is thereby lost. Besides climate change, genetic selection is another driver that plays a role in the emergence of nematodes. Frequent use of a limited number of resistant crop varieties resulted in the rise of nematodes that are less sensitive to these resistance genes."

Mapping the scope of the problem

As nematodes pose an increasing threat to potato and tomato, the project proposal NEM-EMERGE (see box) coordinated from WUR received a major grant from the EU within the Horizon Europe programme in the field of Emerging plant diseases. Helder details what the funds are to be spent on: ‘Among other things, we are going to investigate the current distribution of root-knot nematodes: where exactly are they currently occurring? From southern Turkey and Spain to northern Germany, we are going to take soil samples about every two to three hundred kilometres to investigate the presence of plant-parasitic nematodes. Based on the resulting picture, modellers can predict where we can expect them in five or 15 years.’

Misfunctioning of resistance genes

Helders’ colleague Aska Goverse aims to tackle the instability of resistance genes in plants under higher temperatures in one of the other work packages. ‘We have been working on the molecular mechanisms that underly the (mis)functioning of resistance genes for several years. We have a pretty good view of the factors determining their function for some diseases, but not yet for these plant-parasitic nematodes. In the case of tomatoes, we often don’t know whether the loss of resistance is caused by temperature increase or genetic selection. That makes predicting further developments challenging. Another challenge lies in distinguishing between different populations of parasitic nematodes and determining which ones can still be controlled and which can’t.’

Translating into practical solutions

The researchers will work on solutions in close cooperation with end-users. As the use of pesticides is increasingly restricted within the EU, farmers seek alternative methods. Goverse: ‘Growers require knowledge and practical tools to make a transition towards sustainable agriculture. The EU is steering towards integrated crop management, but what tools are needed to reach that goal? How can we for instance boost the soil’s disease-suppressive potential? At the same time, researchers want to know the demands and the conditions for innovation from an end-user’s perspective. The ultimate goal is to develop solutions that can be put into practice.’

- Unfortunately, your cookie settings do not allow videos to be displayed. - check your settings

Collaboration is equally important

There is no single silver bullet solution for the afore-mentioned nematode problems, Helder warns. ‘We cannot afford to focus exclusively on, for example, new resistant varieties because it is only a matter of time before a new population of nematodes emerges that can break this resistance. We must really focus on a wide range of measures, from plant resistances to more hygienic working practices to the stimulation of natural enemies.’

Finally, he emphasizes that the project involves more than ‘just’ a large subsidy from Brussels. “The collaboration between research groups is at least as valuable. It is already there, but only sparingly. The breadth of the consortium, from growers to universities, gives this project an extra dimension. We hope that this project can be the oil that will greatly boost cooperation between European research centres.’