Wageningen World

Palm oil could be much more sustainable

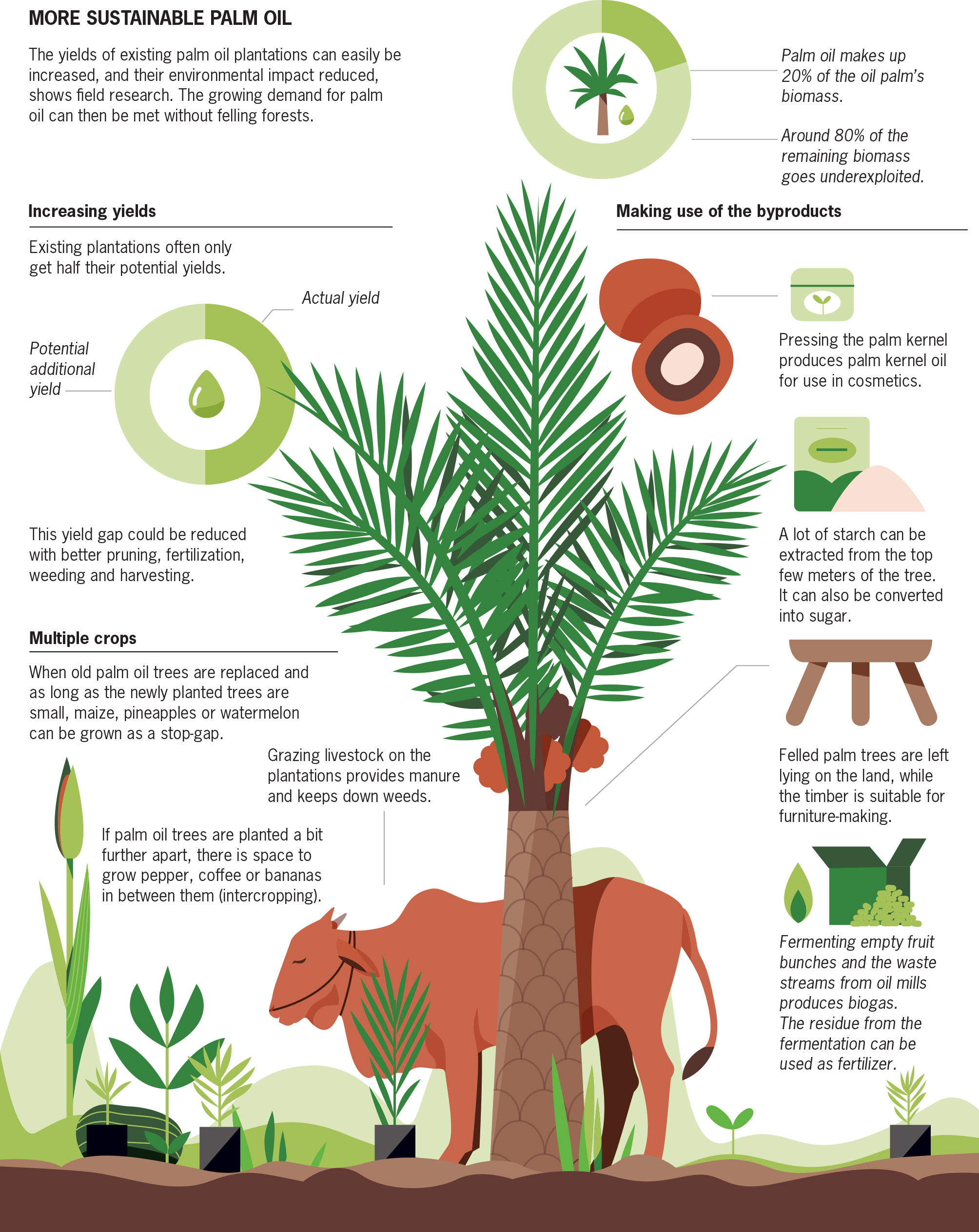

Research in Indonesia shows that it is possible to meet global demand for palm oil without felling forests, thus reducing the environmental impact of palm oil production. ‘We must help both large- and small-scale farmers to exploit the existing plantations more sustainably and efficiently.’

In Indonesia alone – the world’s biggest palm oil producer – more than 10 million hectares of new oil palm plantations have been created since 2000. Many of them replaced other crops such as rubber and rice: oil palms are more productive per hectare with lower labour costs, but about one third of the new plantations are on recently deforested land and vulnerable peatlands. That entails biodiversity loss and drainage, causing the land to dry out. Furthermore, deforestation and drainage cause considerable CO2 emissions. For this reason, the Indonesian government declared a moratorium on deforestation for timber and oil palms in 2019.

Wageningen World

Three tons of oil

Yet palm oil deserves better than this, claim the Wageningen researchers Maja Slingerland and Wolter Elbersen. ‘With its three tons of oil per hectare per year, the oil palm produces far more oil per hectare than alternatives such as soya and oilseed rape – although these crops also produce a valuable protein co-product, unlike the oil palm,’ says Elbersen, a biomass expert at Wageningen Food & Biobased Research. ‘And the oil palm requires less fertilizer and pesticide per litre of oil,’ adds tropical agriculture expert Slingerland, of the Plant Production Systems chair group.

Both researchers have been working on improving the ecological and economic status of the oil palm in Indonesia for many years, in collaboration with farmers, research institutes and the government. Even without felling trees or using virgin peatland, it is possible to meet the growing global demand for palm oil for use in food, Elbersen and Slingerland believe.

Most of the biomass of the oil palm goes underexploited

Existing plantations achieve barely half the theoretically possible yield, calculated Slingerland and Indonesian researchers. And that can be significantly improved, as shown by research that WUR carried out between 2019 and 2023 together with the University of Nebraska- Lincoln and the Indonesian Oil Palm Research Institute. Slingerland: ‘In a trial in six areas with 200 farmers each, we saw increases in production of up to 35 per cent. Farmers started pruning better, and fertilizing, weeding and harvesting more precisely.’

In 2022, WUR began working in the SustainPalm programme with Van Hall Larenstein, IPB University and Lambung Mangkurat University on reducing the ‘yield gap’ and saving land by using different techniques and developing new business models in small-scale experiments with farmers, companies and research institutes. In these ‘living labs’, an exchange of experiences takes place through ‘communities of practice’.

Intercropping

According to these researchers, there is scope for reducing the environmental impact of palm oil production too. One way of doing this is to practice intercropping. The farmers in the trial are experimenting with temporary crops, for example when their oil palms have to be replaced after 25 years. For the first four years, until the new oil palms bear fruit and therefore generate income, crops like maize, pineapples and above all, watermelon, are a promising option. ‘It’s an attractive prospect that we save on land elsewhere like this without losing any palm oil production,’ says Slingerland. ‘What is more, that can generate some nice extra income. We know farmers who even want to stop producing palm oil because watermelons are more lucrative.’

More permanent forms of intercropping, with pepper, cocoa, coffee, bananas or tree species for light timber, are also possible. By planting the palm trees a bit closer together, you can create 15-metre-wide strips in which there is enough light for low-growing crops, says Slingerland. ‘Dozens of small farmers as well as a few large companies are experimenting with bananas, with the enormous leaves staying on the land as fertilizer after the harvest.’

Such experiments sometimes have a positive gender-related impact too, she adds. In Riau, on Sumatra, women make cookies and juice out of pineapples that grow between the palms. ‘And the banana growing in Kalang, in Central Kalimantan, has prompted a lot of women to fry banana chips in palm oil, and sell them at local markets.’

Livestock farming can also benefit the environment and offer opportunities for additional earnings. If cows are allowed to graze under the oil palms that spreads the risks of disappointing harvests and price fluctuations. The animals also eat the weeds, which saves on herbicide, and they provide manure for the oil palms. ‘Of course the livestock can only start grazing on the plantation after five years, otherwise they eat up the young palm trees,’ says Slingerland. She points out that the rising standard of living in Indonesia means that the population is eating more meat. ‘At the moment, a lot of expensive beef is imported from Australia. Homegrown meat could cut costs. We are still studying the effects on oil production, but up to now we are seeing more of a positive influence than a negative one.

Using the land on palm oil plantations for multiple purposes means saving land elsewhere from use for plantations and livestock, not to mention timber. The savings on the purchase and maintenance of that land, the reduced expenditure on import of meat and the reduced environmental impact, including CO2 emissions, will boost the economic and ecological score of the oil palm considerably: that’s the idea. The initiatives also aim at improving the biodiversity on the plantations, by not using herbicides for one thing. ‘We are seeing potential for an increase in subspecies, more carbon sequestration in the soil and an improved soil life.’

Reforesting

Studies are also being done on the idea of not replacing some oil plantations in peatland areas at the end of their lifespan, but reforesting the land instead or preparing it for wet crops such as jungle rubber, sago, reeds and rice, by raising the water level. ‘We are monitoring both intensification of the existing plantations, and reforestation and other farming options on phased-out plantations. One of the challenges is for the small-scale farmers to get the same income from the alternative crops as they used to get from oil palm. We also calculate the savings on greenhouse gas emissions,’ says Slingerland. There are also numerous byproducts of palm oil that could be better exploited, with both environmental and economic benefits, claims Elbersen, who has been doing research on this with his fellow researchers for years. ‘Don’t forget that the oil constitutes only 20 per cent of the oil palm biomass. About 80 per cent of the remaining biomass still goes largely unused.’ Besides the crude palm oil that is extracted from the palm fruit, the palm kernel can be cracked and pressed. ‘That produces valuable palm kernel oil, which is used in cosmetics such as lip balm.’

The oil palm can meet some of Indonesia’s demand for starch

The watery effluent from the oil mills can also generate income. ‘That is currently discharged into rivers or returned to the land after anaerobic treatment. That gives the soil some nutrients, but it also releases methane when processed in open ponds.’ It is smarter to ferment the waste together with the empty fruit bunches, as Elbersen and his colleagues have tested. ‘Biogas produces enough energy for the palm oil mill. Currently they burn the mesocarp fibre and shells for that purpose, whereas you could sell it for making biobased products, for example, or generating electricity, replacing coal. And even the digestate, the waste product of the fermentation process, is usable too. It is a nice, stable fertilizer which provides both nutrients and organic matter that improves soil quality.’ The researchers are going to do further tests on this circular process with IPB University in Bogor in an IPB trial mill on a demonstration scale.

Starch and wood

And even the discarded palm trunks could be of more value. When an oil palm plantation is felled after 25 years, the trees are left to rot in the field. ‘Decomposition products and nutrients trickle back into the soil, but it could all be made much more circular,’ says Elbersen. The researchers discovered that you can extract a lot of starch from the top of the 10-metre-tall trunks: they estimate that up to five tons of starch is stored in a hectare of old palms. ‘That could meet some of the demand for starch in Indonesia or in other markets. You can also convert the starch into sugar. Indonesia currently imports sugar,’ says Elbersen. The researchers estimate that oil palm sugar could theoretically halve those imports.

And then there’s the palmwood itself: about 70 cubic metres per hectare. Elbersen places pieces of palm veneer and a block of palmwood on his desk. ‘This is lightweight wood that is suitable for building or for furniture making. The CO2 stored in it then stays put for another 50 years at least, rather than escaping through rotting or burning. We should try to interest IKEA in this,’ thinks Elbersen. ‘The products could be included in the existing sustainability certification systems for palm oil.’

Reducing the footprint

But if the suggested improvements prove viable and are rolled out on a large scale, wouldn’t there be a downside that more forest would be felled because the big companies would smell a profit? ‘We are not directly addressing deforestation but trying to reduce the footprint of palm oil,’ says Elbersen. ‘Indonesian policy is based on a moratorium on palm concessions. Deforestation has gone down dramatically, but is not yet at zero.’

Slingerland agrees that you don’t have to cut down forest to boost production. ‘Deforestation must stop of course. We focus on measures that make that possible economically and ecologically.’ In the time remaining for the project, the researchers want to calculate the environmental and economic advantages more precisely, including the amount of agricultural land that is spared

Both large concession holders and small farmers, who account for 40 per cent of the palm oil production, should benefit from the Wageningen research. One option, for instance, is to admit landless farmers with experience of growing watermelons onto the oil palm plantations. ‘Then the oil palm farmers can leave that work to them,’ says Slingerland. ‘But the main thing is that we shouldn’t dwell on everything that goes wrong.’ Elbersen: ‘We shouldn’t just say, “Thou shalt not destroy forests”, but should help both large- and small-scale farmers to exploit existing plantations more sustainably and efficiently.’