Project

Vegetable agro-biodiversity in Northern Vietnam

It is not clear how farmer’s decision on seed access, production and storage and strategies in conserving on-farm agro-biodiversity lead to household nutrition diversity and income generation. This research aims to analyse farmers’ seed choices, jointly test practices to enhance quality of self-saved seed, and analyse factors influencing intra-species diversity in vegetables within ethnic minority communities in Northern Vietnam. All is to understand how agro-biodiversity is shaped and can be maintained in and by these communities while enhancing nutrition/income security.

Background

Seeds can be accessed through two seed systems. The formal seed system provides certified seeds from the public and commercial private sector. The informal seed system usually refers to the local seed provisioning and acquisition by farmers, through which landraces (i.e., local cultivars being improved by traditional agricultural methods) and local cultivars flow (Almekinders, 2000).

The agro-biodiversity is the biodiversity in agriculture, a sub-set of a general biodiversity, which commonly has three dimensions: diversity within species, between species and at ecosystem levels (e.g., Martínez-Jauregui et al., 2020; IBPGR, 1990). Agro-biodiversity supports farmers in access to diverse food and so dietary diversity that the two forms of diversity are an asset to household food security. Vegetables are rich in minerals, vitamins and sometimes proteins. Thus, strengthening access to a wide range of vegetable seeds that supports production of a wide range of quality products for home consumption and/or income generation is essential. Given that some communities have little access to the formal seed system focus will be on seed production and storage with emphasis on those species that have a specific role in dietary diversity.

Project description

This PhD is linked to a research for development project that tries to improve nutrition in selected sites in Northern Vietnam (relevant to this study) through strengthening vegetable seed systems. Current nutritional diversity of the studied ethnic communities in Northern Vietnam was found to be limited and showing clear gaps. Thus, nutrition rich crops were selected for the study that fill a gap in observed nutrition diversity; further criteria were that crops should differ in terms of species and reproductive biology and face seed related problems (i.e., in seed preservation, seed handling and storage). In the end, three different crops (H’mong mustard, French bean, and pumpkin) have been selected. We have been conducting three studies. The first study is to figure out what drivers are present and what their roles are in shaping species diversity of vegetables grown on-farm and seed sources; The second study aims to analyse the role of distinct factors in mediating farmer’s decision on adopting, adapting, adjusting or non-adopting practices for enhancing seed quality of self-saved seed. In addition, this study would allow the researcher to acquire insights whether the problem of self-saved seed quality per se hinders farmer’s incentive in saving seed and seeking for alternatives. Finally, the third study will analyse both external seed source and saved seed management practices in co-contributing to within-species diversity at the household and village and/or community level.

Results

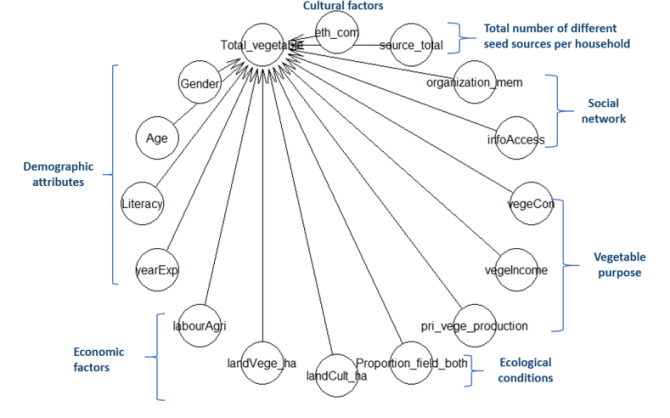

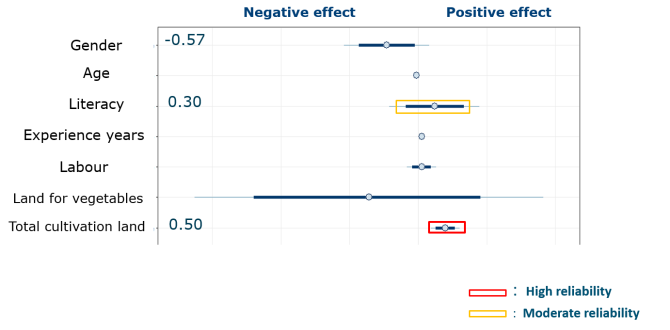

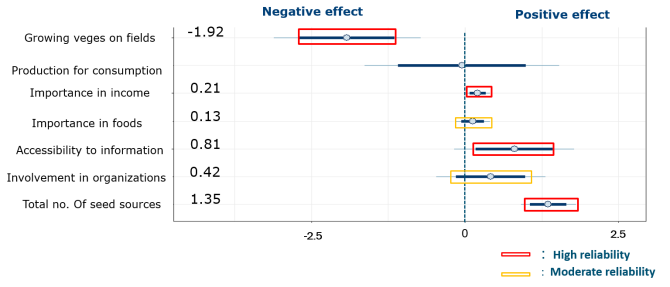

We conducted a cross-sectional survey combined with qualitative analyses to unpack the drivers in vegetable and seed diversity in Northern Vietnam, a hot spot of ethnic diversity and nutrition insecurity in the country. The study showed that in the region 86 nutrition dense vegetables were grown out of 106 vegetable types grown in total. Out of 106 vegetable types, 41 (ca. 38%) were grown by only 1 to 5 households, thereby making a large variation in vegetable portfolio among households. The outcome of running a Bayesian regression model, revealed the factors having positive effects on vegetable diversity including the importance of vegetable in households’ foods and income, farmer’s accessibility to information sources of seeds, family’s involvement in social or mass organizations, cultivation land area, and total number of seed sources where farmers acquired seeds from. In addition to these, the intention to grow vegetables in fields (i.e., instead of home-gardens) had a strong negative effect on vegetable diversity, which was likely attributed to the distance of fields from home, thereby making difficult for farmers to take care of various crops, and the priority for a larger scale vegetable production. Better access to markets did not lead to a consistent gain or erosion of vegetable profiles as in addition to economic factors social and cultural drivers played more key role, in farmer’s seed choice. In terms of seed source selection, trust was a key driver in farmer’s choice. While self-saved seed was the main vegetable seed source, better access to input markets and development of vegetable cooperatives increased farmers’ intention to source seed from markets and adoption of new cultivars.