News

H5N1 bird flu virus replicates in bovine airway epithelial cells

European highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 strains are able to replicate in bovine airway epithelial cells cultured at air-liquid interface. This is the conclusion of research conducted at Wageningen Bioveterinary Research, the Netherlands. “Our experiments show that multiple European H5N1 virus isolates can replicate in bovine airway epithelial cells in the laboratory. An observation which has not been reported before as far as we know”, states PhD researcher Luca Bordes.

Since 2020, a global increase in the number of outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 was detected in poultry and wild birds. In addition, HPAI was found in a wide range of mammalian species. In most cases these were carnivores that were exposed via direct contact with infected wild birds. Ruminants were previously not considered a natural host species for HPAI viruses. However, in March 2024 multiple outbreaks of HPAI H5N1 were detected in goats and cattle in the United States. In response to this development, the Dutch ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV) commissioned Wageningen Bioveterinary Research (WBVR, part of Wageningen University & Research) to conduct research into the susceptibility and permissiveness of bovine epithelial cells to infection of European H5N1 strains. This research was financially supported by LNV and the research programs Next Level Animal Science and ERRAZE@WUR of Wageningen University & Research.

Bovine airway epithelial cells

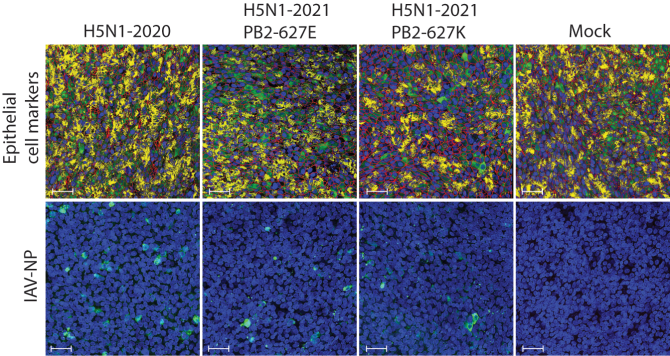

To test the susceptibility and permissiveness of bovine epithelial cells to infection with European H5N1 strains, the WBVR research team used primary bronchus-derived well-differentiated bovine airway epithelial cells (WD-AECs) cultured at air-liquid interface. These bovine WD-AECs were inoculated with three HPAI clade 2.3.4.4.b H5N1 virus isolates derived from poultry or red fox as hosts. “We detected rapid increases in viral genome loads and infectious virus during the first 24 hours post inoculation for all three viruses tested, without substantial damage to the infected cells”, says researcher Luca Bordes. Three days post inoculation the infected bovine cells were still detectable by immunofluorescent staining. However, as the virus titers dropped rapidly over time, the researchers conclude that virus propagation was not very efficient.

“These data indicate that multiple lineages of HPAI H5N1 may have the propensity to infect the respiratory tract of cattle. As we used European strains of the bird flu virus, we conclude the infection of bovine cells is not unique to the North American strain of H5N1”, states Bordes. “Furthermore, our research supports the extension of the surveillance efforts with regards to avian influenza surveillance in ruminants.”

Preparedness

In the US, HPAI in cattle is mainly associated with virus detection in milk. Analysis of the H5N1 virus in cattle showed the virus was of avian origin and closely related to wild birds. However, despite ongoing surveillance HPAI has thus far not been detected in European cattle. According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), transmission of HPAI H5N1 to humans is possible through direct contact with infected animals, but human-to-human transmission remains unlikely with the current genetic composition of HPAI H5N1.

At present, surveillance of avian influenza is largely focused on wild birds, poultry and wild carnivorous mammals. However, the H5N1 outbreaks in ruminants in the US and the results of the current study support extension of serological surveillance to include ruminants. The study into susceptibility and permissiveness of bovine epithelial cells for avian influenza underlines the benefit of WD-AEC cultures for pandemic preparedness. “These cultures provide a rapid and animal-free assessment of the host range of an emerging pathogen”, according to researcher Nora Gerhards.

Future research

The knowledge gained from this research has its limitations, stresses Bordes. “Based on our current data we cannot predict the likelihood of European H5N1 viruses spreading to ruminants or if transmission between ruminants is possible. For this further research is required”, he concludes.