News

Europe can set up its own – sustainable – textile sector

European countries have lost their textile production sector in recent decades due to competition from cheaper Asian producers. Europe can develop a new sustainable textile sector if the EU stimulates the production and processing of natural and biobased fibers, says Sanabel Abdulbawab, Researcher, BBP Biorefinery & Sustainable Value Chains at Wageningen Food & Biobased Research.

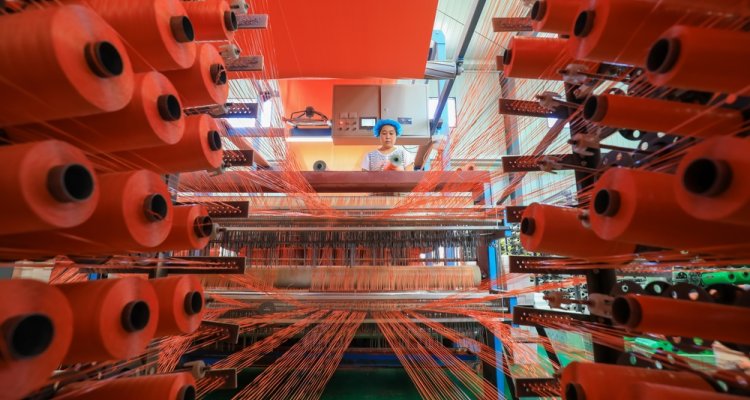

The production of clothing takes place in international chains, where the fibres are produced in country A, the fibres are processed and mixed in country B, they are spun in country C, after which the yarns are used for textile production in country D. Europe plays a small role in these global production chains, due to lower production costs and wages and laxer legislation elsewhere. Furthermore, two-thirds of the textile consist of synthetic polyester fibres. These fossil-based fibres are controlled by a few key players globally.

Taking the lead in the transition

Europe can only regain a market position in the production of natural, sustainably produced fibres, Abdulbawab explains. She refers to the production of fibre-rich crops such as flax, hemp, nettle, wool and manmade cellulosic fibres. There are also many companies in the Netherlands that recycle discarded cotton to make textile fibres again. And she sees a niche market for biobased polyester, made from plants.

‘Because it is a global sector, we can have the natural fibers spun and dyed outside Europe. But in this case we do control some of the fibers and resources for clothing production and put it back into EU market. Europe can take the lead in the transition to the biobased textile industry.’

Clothing made of biobased fibres is currently more expensive than cheap fossil-based textiles from Asia. Because the textiles are often of poor quality and cheap, the average European uses 26 kilos of textiles every year, 16 kilos of which are thrown away. 70% of this ends up in landfills or is incinerated, 20% waste is now often exported to low-wage countries and 10% is recycled. ‘Chemical recycling of mixed textile waste is currently not profitable, because most textiles consist of combinations of different fibres, which makes separating the fibres too complex and expensive.’

Yet there are companies in Europe that produce fossil-free textiles or that reuse polyester textile. Abdulbawab mentions the example of the company Saxcell located in Enschede. Saxcell chemically recycled rich cotton textile waste and turn it to lyocell, a biobased cellulosic fibre.

The European Union can support the biobased textile sector and similar producers with legislation and subsidies, the researcher says. She sees many opportunities. ‘European member states can subsidise the production of fibres from hemp, they can encourage the use of PEF or reuse of PET in chair and sofa upholstery and they can tax fossil-based fibres, so that the influx of polyester clothing decreases.’

Rethink Textile Hackathon

And last but not least: they can stimulate new concepts and applications of sustainable textiles from natural resources. And that is exactly what WUR organised last month. During the Rethink Textile Hackathon, student teams came up with new textile applications from plants and waste. Abdulbawab gave a presentation about textile processing on November 19 during the final day of this hackathon.