News

All the world’s soils in one app - iSQAPER (SLM)

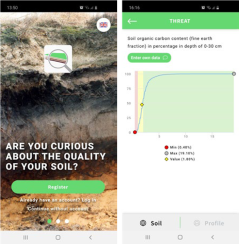

An app that presents all the soils in the world and also gives advice on how to improve those soils - that is SQAPP. The app was developed by Wageningen researchers together with a large international team. Farmers have already discovered the free app. “Shortly after SQAPP had been launched, we found it had already been used in 8,000 places around the world.”

There is an awful lot known about soils but that knowledge is not accessible for farmers

Soil is the farmer’s most important and valuable input. It is therefore important to keep the soil healthy, but that is easier said than done. For a start, you need to know what the quality of your soil is. That is why Wageningen researchers joined forces with a large team of European and Chinese scientists in a project called iSQAPER: Interactive Soil Quality Assessment in Europe and China for Agricultural Productivity and Environmental Resilience. This collaboration resulted in the Soil Quality App (SQAPP). The app gives a score for the soil quality and recommendations on how to make improvements. The app can be downloaded free of charge by anyone and is already operational. Project manager Luuk Fleskens of Soil Physics and Land Management at Wageningen University & Research is pleased with the result.

All the world’s soils

SQAPP is the product of five years of intensive collaboration between scientists in twelve European countries plus China. Fleskens: “We were a very large team working on a huge project. With such large multilateral projects, you can never be sure whether you will be able to put everything together. One team was working on soil biology while another was researching climate models. It’s always a challenge to integrate all those different research results, but SQAPP is that integration. It was really nice to work on something that specific.”

The app was not limited to the soils found in the countries working on the project; it covers all the soils that can be found around the world. That sounds like an impossible task. In fact, an awful lot is known worldwide about soils - that knowledge is stored in databases and in soil maps showing areas with soils that have approximately the same physical and chemical properties - but that knowledge is only accessible to scientists, not farmers.

‘Changes in the soil structure and composition are a slow process’

There are other soil apps around, but what makes SQAPP unique is the advice aimed at improving the soil.” The recommendations are largely based on the Long-Term Field Experiments, as they are known, which are being carried out in various countries including Switzerland, the United Kingdom and China. Changes in the soil structure and composition are a slow process. Field trials over long periods of twenty years or more can demonstrate soil changes in the longer term. These trials consider variations in the application of fertiliser (intensive or less so), cultivation method (strip cropping or monoculture) and soil management practices (ploughing or not ploughing).

Fleskens:

“Eventually we used all this information to create a prototype in partnership with an app developer.”

240,000 measurement points

Wageningen students played a significant role in determining the final structure of the app.

“When the students did their annual practical week in Spain, we sent them into the field with the prototype. They came back with loads of tips on how to improve the app’s structure and make it more user-friendly. The ideas were so useful that we took them on board,”

laughs Fleskens.

“That’s the advantage of working at a university – you can get young people involved who grew up using apps.”

SQAPP is largely based on data from Soilgrids, a map of soil indicators that contains 240,000 measurement points describing soils from around the world in terms of the soil type, carbon content, acidity, density and so on. Despite the vast number of data points, the analysis of the soil is still an estimate. As a user, you can’t be entirely sure the information the app gives you is correct. For example, Soilgrids doesn’t allow for the soil management history – how the field was managed in the past. This limitation was taken into account when the app was developed and users can add their own information.

SQAPP is largely based on data from Soilgrids, a map of soil indicators that contains 240,000 measurement points describing soils from around the world in terms of the soil type, carbon content, acidity, density and so on. Despite the vast number of data points, the analysis of the soil is still an estimate. As a user, you can’t be entirely sure the information the app gives you is correct. For example, Soilgrids doesn’t allow for the soil management history – how the field was managed in the past. This limitation was taken into account when the app was developed and users can add their own information.

Fleskens:

“If a farmer has measured the soil density in his fields and that value doesn’t match the value in the app, he can enter his own latest value. Then all the recommendations will be adjusted to take account of this new data. This information could perhaps even be used to improve soil data in the future.”

Google Maps for soils

When you use the app for the first time, it feels like you are opening Google Maps. Click on your own location and you’ll see a profile with various characteristics such as the soil density, organic matter, soil type (clay, loam, sand), water retention capacity, acidity, and so forth. The app also lists the threats to the soil, such as erosion, salination or excessively high lead concentrations. The user can specify which crops are grown and whether crop protection agents are used. Based on all the soil indicators and the information entered by the user, the app gives the quality of the soil as a percentile of all the soils in the same soil zone. A percentile score of 67 per cent, for example, means that 33 per cent of the soils in that zone are doing better. The app also shows where the problems lie. SQAPP has a list of 89 recommendations it can draw on for tackling those problems. The list was put together using input from all the partners in the participating countries.

Fleskens:

“Let’s say you’re a farmer and you have a problem with the carbon concentration, which is a key yard stick for the health of your soil. You may get ten recommendations, three of which are new to you. For each of those three recommendations, you will also see various specific examples. It’s likely there will be at least something you can use in amongst them.”

There are other soil apps around, but what makes SQAPP unique is the advice aimed at improving the soil.

Crop protection agents

The project ended in 2020. SQAPP is the end product of that process, but Fleskens also sees the app as the start of a new period. “We’ve incorporated an overview in the app of all the pesticides that are available in Europe. Farmers can say which ones they use. They then get information about the persistence of the pesticide in the soil. If a farmer sees that their pesticide stays in the soil for a really long time, they know they would be better off not using that product. This is the first time this aspect has been made so clear to users.” Fleskens would also like to include the degree of toxicity of certain pesticides and other crop protection agents in the

app. The changes in the soil due to climate change are another very interesting aspect, in his view. “As climate zones shift, it will affect the quality and structure of soils. Erosion could increase, or conversely decrease, the water retention capacity could be altered and there are undoubtedly other changes to be expected due to the climate. These are all aspects you could include in the app. In fact, the possibilities of SQAPP are endless.”