Wageningen World

Greenhouses can’t do without gas yet

Because of the energy crisis, greenhouse horticulturists are heading for uncertain times. Greenhouses consume nine per cent of the natural gas in the Netherlands, and alternatives are not readily available. ‘But the heating requirements of a typical horticultural business can be halved’.

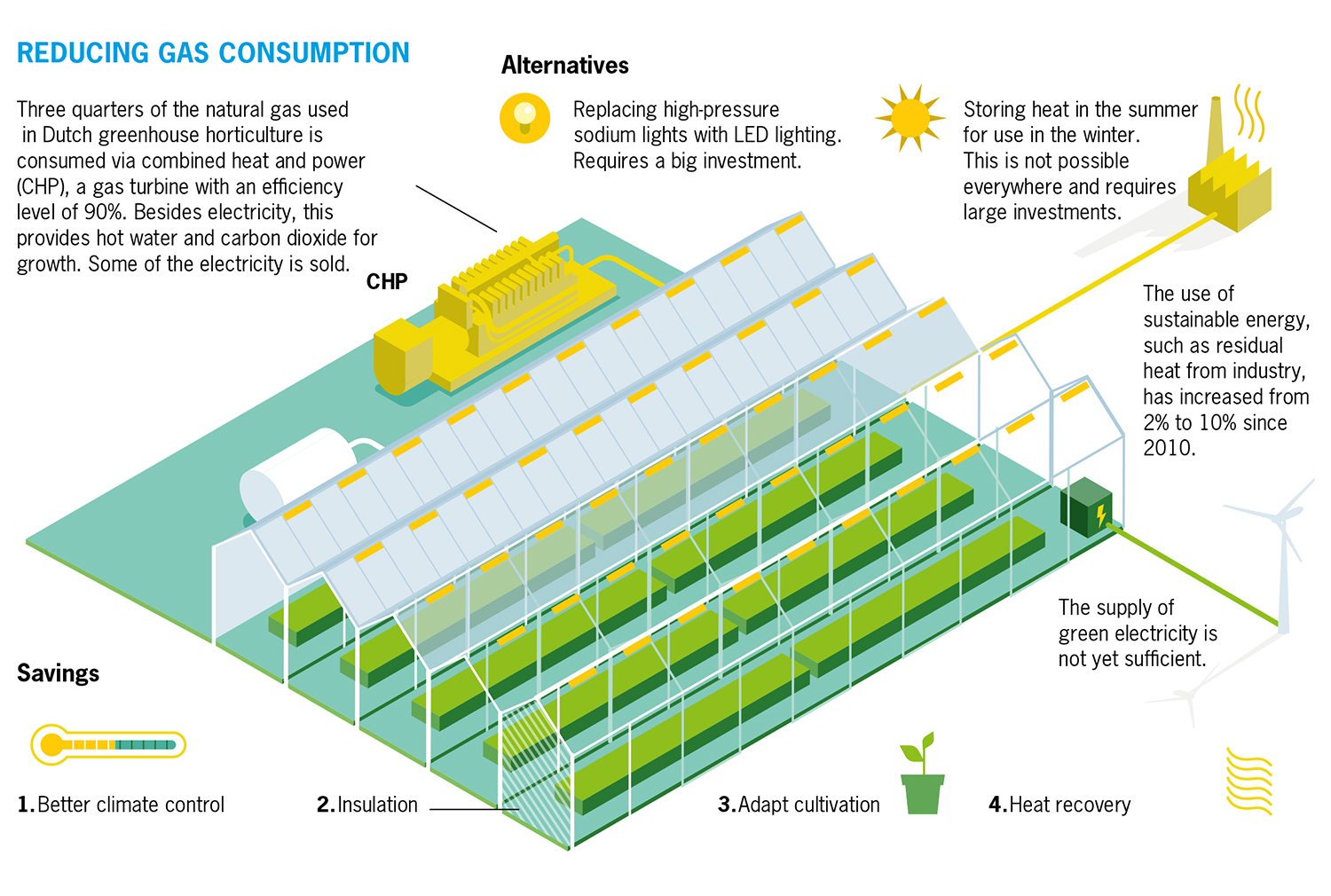

Photo above: Shutterstock | Infographic: Jorris Verboon

Growers of tomatoes, cut flowers and pot plants are no different from the average household; their greenhouses use a lot of gas and electricity, especially in winter, for heating and lighting the plants. Prices have recently risen rapidly, especially since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and the reduction in gas supplies from Russia. Whether or not this will put horticulturalists in the red depends mainly on how long this energy crisis lasts, according to a survey by greenhouse horticulture organization Glastuinbouw Nederland. Before 2022, 75 per cent of the greenhouse horticulture companies had fixed the price for at least some of their energy in longer-term contracts with energy providers. Nevertheless, 38 per cent of greenhouse horticulturalists expect to have difficulty paying their bills by the end of 2022. Some growers decided last winter to heat less, switch off the lights or not to use all their greenhouses.

Winter break or not

Many more may do this next winter. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy is working on a shutdown plan for Dutch businesses, should real shortages occur. The plan includes compensation for greenhouse horticulture companies that voluntarily reduce their energy consumption. This will enable growers to assess what would be the most economically sound course of action: to continue growing plants through the winter or to take a break. ‘That is the kind of thing entrepreneurs are wondering about under the present circumstances,’ says Frank Kempkes, a researcher in Energy and Greenhouse Climate at Wageningen University & Research in Bleiswijk. He is the project leader of a number of demonstration greenhouses showcasing how greenhouse horticulture can be more energy efficient. ‘At the current gas price of around two euros per cubic metre, you can’t really break even anymore. There have already been rose growers who turned off the heat in their greenhouses last winter. Roses can withstand such a period perfectly well, but other types of cut flowers cannot. Potted plants can be kept a little cooler for a few months, but you can’t turn the heat off completely. And it will delay growth and mess up the company’s planning.’ Growers have to decide far in advance what risks they want to take with a crop, says Kempkes. ‘For an illuminated tomato crop, the young plants are moved into the greenhouse at the beginning of August and harvesting starts early October. Once the plants are established, and you have been investing in substrate, fertilization and care for months, you cannot just turn off the heat when the price of gas goes up. You will suffer massive losses if you do.’ The demonstration greenhouses in Bleiswijk have shown in the past few years that considerable energy savings are possible in, for example, the cultivation of strawberries, gerbera, freesia and pot anthurium. Experience has been gained with better insulation, heat pumps, efficient LED lighting, dehumidification and precision climate control. One of the challenges of optimum insulation with little ventilation is air humidity, which can cause fungal infections if it gets too high. ‘For the freesias, we have adjusted the lighting better to the growth stage,’ says Kempkes. ‘A young plant gets little light, and a big one more, up to a certain maximum. By doing that, we have significantly reduced electricity consumption for the lamps, and growers have become more aware that more light is often pointless.’

Green electricity

The demonstration greenhouses do not use gas: their heating and lighting are electric. And that is the way to go, Kempkes thinks. ‘Preferably on green electricity, but that is either not available or not affordable yet, and it is impossible for individual growers to organize it with wind turbines and solar panels on their own land. Hydrogen is an option as a fuel, but that is still a distant prospect. And in a lot of future scenarios, hydrogen is seen as primarily an energy source for industries that work with very high temperatures, such as the chemical, glass and steel industries.’ Greenhouse horticulture has made great strides in energy saving over the past 20 years. More is being produced per square metre using less energy. But there are even more possibilities, says Kempkes. ‘When you add it all up, the heating requirements of a typical horticultural firm can be halved with insulation, heat recovery and smarter cultivation. Storing heat in the ground can also yield savings, because this technology uses the heat surplus in summer to make up for the shortage in winter.’ A few pioneers have already switched from gas to heat storage. Orchid grower Van der Hoorn in Ter Aar had 15,000 square metres of gas-free greenhouse built in 2006, with lighting provided by green electricity. The cultivation of butterfly orchids takes a year, six months of which are spent at a tropical temperature of 28 degrees and six months at 19 degrees to stimulate flower formation. During the cold period, the greenhouse is heated by means of a heat pump, and the resulting cold is stored in the soil to be used in the summer to cool the greenhouse. Kempkes: ‘In the Netherlands, the sun provides the equivalent in energy of 100 cubic metres of natural gas per square metre. Growers consume an average of 30 cubic metres per square metre each year, so the sun supplies much more than the horticultural sector needs. Sadly, it is all concentrated in the summer months.’

Seasonal heat storage

Storing summer heat sounds like the perfect solution, but to Kempkes it is just one of the options for saving energy. ‘It will be a long time before seasonal storage of heat is standard practice, and it requires big investments in equipment and construction. Storage takes place in aquifers in the soil, but you can’t do that everywhere, because the groundwater is sometimes too deep or too fast-flowing, or you are not allowed to used it.’ Heating is just one of the things growers need to make crops grow and flower properly; artificial lighting is at least as important for many crops. The standard lighting in the greenhouse is a variant of old-fashioned street lighting: the high-pressure sodium lamp. This produces bright orange-yellow light but also a lot of heat, so it is not very efficient. Kempkes: "Modern LED lighting can halve electricity consumption, but it also means a big investment.’ Finally, greenhouse farmers can consider turning the thermostat down a few degrees, or switching between crops: growing pot plants in winter and peppers in summer, for example. Kempkes: ‘You can grow many crops at colder temperatures, but it also slows their growth, and lowers both yields and quality. The consumer won’t like that. We switch crops in our demo greenhouse, but in daily practice that is not easy. Pot plants are often grown on concrete floors and sometimes even on tables. Taking out all the tables for six months is a big job, besides the extra investment.’

Coping with setbacks

Investing in glasshouse horticulture presents entrepreneurs with difficult choices, says Pepijn Smit, a researcher at Wageningen Economic Research and author and project leader of the annual Energy Monitor for Dutch Greenhouse Horticulture. ‘On the one hand, the sector wants to stop being dependent on natural gas as soon as possible. On the other hand, that first has to be feasible, not least financially. There are dark clouds hanging over the sector’s future. Growers don’t know what will happen this winter, let alone in the next two years. Some companies still have reserves for coping with setbacks, but they are not inexhaustible either.’ And that is in spite of the fact that the sector has developed well, says Smit. ‘The upscaling and professionalization of recent years have made it possible to invest in sustainable solutions.’

The Energy Monitor for Dutch Greenhouse Horticulture provides an annual overview of the energy accounts of Dutch greenhouse horticulture and the energy sources it uses. Smit: ‘The use of sustainable energy has grown steadily, as has the purchase of energy such as residual heat from industry, which means the greenhouses do not themselves emit CO2.’ Since 2010, the proportion of energy that is sustainable has increased from 2 to 10 per cent. ‘If you want that proportion to grow even further, you need alternatives that are available and affordable. Affordable sustainable electricity should be one of them.’ According to Smit, the role of electricity is sometimes forgotten in discussions about greenhouses and gas consumption. Lighting is essential for year-round production. Growers use combined heat and power (CHP) for this purpose: a mini power station with an efficient gas turbine that produces electricity, hot water and carbon dioxide for the growth, all of which benefit production. In addition, a significant amount of the electricity produced by CHP is sold for use by other energy consumers in the Netherlands.

Selling electricity

In terms of energy consumption and costs – 1.3 billion euros annually – the greenhouse horticulture sector is up there with the chemical industry and oil refineries, writes the ABN AMRO bank in a recent report. Greenhouse horticulture is a major consumer, accounting for nine per cent of the natural gas in the Netherlands. Three-quarters of that gas fuels combined heat and power plants, which cover no less than 11 per cent of the country’s electricity needs. Smit: ‘The greenhouse horticulture sector sells more electricity than it uses itself, particularly at times of peak demand in the network, for example on winter mornings or when there is less wind or solar power available. CHP plants can respond very fast to changes in electricity consumption, much faster than a coal-fired plant.’ That is food for thought, says Smit: if you get the greenhouse horticulture sector off the gas, growers will have to source their electricity, heat and carbon dioxide for growth elsewhere. ‘If electricity from a power station is expensive, it may be more attractive to buy expensive natural gas and convert it into heat and electricity in CHP plants. Cogeneration (CHP) in greenhouse horticulture is remarkably efficient, with a utilization rate of over 90 per cent.’ At present, cogeneration, combining heat and power, has several commercial advantages, says Smit. If gas consumption and emissions in greenhouse horticulture are to be reduced, more sustainable electricity, heat and CO2 must become available. ‘Once there are affordable alternatives, growers will be happy to switch to them and reduce their gas and CHP consumption.’