News

Algae: unexpected allies in the mission for a circular future

Under the right circumstances, tiny algae can multiply at extreme rates which means that all kinds of sustainable applications are becoming more feasible. But while researchers in Wageningen are unravelling more and more secrets about algae production, the scaling up to a fully-fledged algae bioreactor is still not that easy.

Many remote islands have a challenge in common: they are hardly ever self-sufficient. Numerous essential products – from food to fuels – must be brought in from outside. This makes the islands hugely dependent on other countries and, of course, it also results in a lot of CO₂ emissions by container ships.

But what if you were able to produce some of these products on the island in a sustainable manner? Scientists at Wageningen have come up with just such a production process, with a few inconspicuous organisms playing the starring role: microalgae. These small powerhouses – most are even smaller than a single red blood cell – can multiply at extreme rates under the right circumstances. Where a palm oil plantation of one hectare produces about 6,000 litres of oil annually, an algae producer can expect to produce about 35,000 litres in the same period.

Fish food and meat substitutes

The great thing is: these microalgae are also a good source of fats and proteins. This means that all kinds of interesting applications are becoming feasible, explains Professor in Bioprocess Engineering René Wijffels “For example, you can convert the microalgae into biofuels to ensure the sustainability of flights to and from the islands.” This production process is currently still too expensive, but a number of other applications are already possible in the short term. Microalgae are very suitable as sustainable feed for fish farms or meat substitutes, for example.

We could convert the microalgae into biofuels to ensure the sustainability of flights to and from the islands

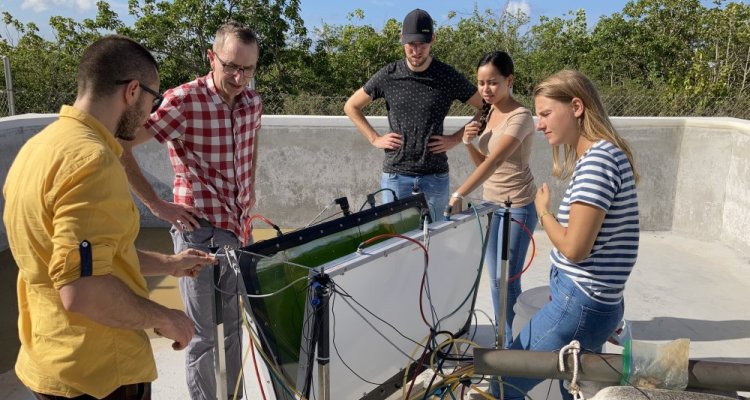

In recent years, Wijffels and his colleagues have been looking for somewhere to produce these microalgae on a large scale. They built a test bioreactor on the island of Bonaire, partly at the request of the local authorities. They then started the search for a ‘closed system’: an algae bioreactor that runs completely on raw materials that are available locally. Wijffels: “Algae are extremely suitable for this, as they primarily need seawater, CO₂ and sunlight. These are inexhaustible raw materials which are present in abundance on tropical islands.”

Keep it cool

But the road to a fully-fledged algae bioreactor is not without problems. The researchers gradually came up against a serious scientific challenge: microalgae do not like high temperatures. If the temperature in your algae bioreactor rises too much – a real problem on a tropical island – the harvest is lost. You can, of course, cool the bioreactor, but this costs a lot of water and electricity which doesn’t fit in the ideal picture of a sustainable closed system.

In recent years, two PhD students– Robin Barten and Rocca Chin-on – have been looking for ways to make algae suitable for the tropical temperatures on Bonaire. First of all, in the laboratories at Wageningen, Barten studied which kind of microalgae is the most resistant to heat. After a rigorous selection process, he arrived at Picochlorum sp., a microalga that occurs naturally on Bonaire. “This is a very robust microalga with a good tolerance against high temperatures and salt concentrations, and moreover it’s one of the fastest growing microalgae in the world,” explains Barten. “It’s also great that it already occurs in the environment, as you don’t want to run the risk of introducing a different type of algae into nature.” Not an unimportant fact here: Picochlorum sp. consists of up to 50% nutritious proteins.

By means of an evolution process, Barten made the Picochlorum sp. even stronger. For a year he produced ‘his’ algae type at slightly higher temperatures each time. Most of the algae died in this experiment, but Barten was only interested in the few survivors. As, by repeating this experiment many times, you are ultimately left with the algae that are extra heat resistant. Barten: “Thanks to this breeding process, Picochlorum sp. can now withstand about 2.5 degrees of extra heat.” The microalgae can now survive up to 47.5 degrees Celsius, but grow most quickly around 40 degrees Celsius.

In the meantime, Chin-on worked on Bonaire on a new prototype of the bioreactor, the test facility in which the algae are bred. Cooling also plays a major role here. Chin-on decided to construct the breeding system in a V-shape, so that the whole bioreactor can sit in water if the temperature rises. The temperature in the water fluctuates less than on land. Chin-on: ‘It sits in water at around 30 degrees Celsius. This means that this bioreactor is also suitable for algae that are slightly less heat resistant than Picochlorum sp in principle.’

Scaling up still a bottleneck

Although scientists have unravelled more and more secrets about algae production in recent years, scaling up to a fully-fledged algae bioreactor on Bonaire is still not that easy. According to Wijffels this is mainly a financial problem: there are few large companies on the island who can develop the Wageningen test facility into a profitable operation. Bonaire’s economy is mainly based on tourism, and there is very little large industry.

To solve this problem, Wijffels proposes to combine the recent scientific breakthroughs into a fully working demonstration model. This kind of mini bioreactor must convince investors – if necessary from other countries – to expand algae production further. Wijffels hopes that authorities, companies or scientific funding bodies will be prepared to finance this demonstration model. “This is the best way to plant a seed,” says Wijffels. “Ultimately, it’s in Bonaire’s interest too as it means that the island can becomes more self-sufficient and the economy more diverse. The concept can then also be applied in other locations: Bonaire can be used as a model lab for this sustainable circular technology.”