Blog post

Emerging components of area-based aquaculture governance

By Simon Bush

Solving complex problems in the aquaculture sector requires integration between actors that don’t normally interact. Understanding how these actors can interact and contribute to area-based management was a key goal of the mid-term meeting of the SUPERSEAS project, held in March 2018 at the Mekong Delta Development Research Institute of Can Tho University, Vietnam.

Area-based aquaculture management is based on the principle of ‘moving beyond the farm scale’. But this does not just mean increasing the spatial ‘area’ under management, based on a watershed or set of shared resources. Area-based management also means incorporating a number of governance processes that directly influence, but extend far beyond, the level of the farm.

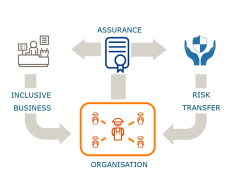

At the half way mark of the SUPERSEAS project, research results indicate there are four interrelated governance components to area-based management (as summarized in Fig. 1).

First, how farmers organize to respond to systemic environmental risks related to disease and water quality remains a key factor of any area-based approach. However, exactly how farmers organize depends on the scale of their collective or shared production risks. As PhD researcher Mariska Bottema describes, cooperation should be defined by the socio-spatial extent of farmer networks within which the perception of risk is homogenous, and nested socio-spatial areas should been seen as building blocks to the management of wider landscapes.

Second, any actions taken at the farm level need a level of assurance that they are in fact contributing to the mitigation of production risk. Risk assurance tools, including certification, have traditionally been developed for the farm scale with the danger of creating a disproportionate burden of compliance on smallholder farmers. However, new assurance models appear more promising, including government-led monitoring programs of common resources supported by yield-gap models.

Third, once assurance is in place, risk transfer arrangements can be designed. Key to these arrangements is that they can reduce information gaps between what the presumed and actual production risks are. Once validated information is available, external (insurance company) and mutual (farmer-led) insurance arrangements can be developed.

Fourth, supermarkets also face risks in terms of matching demand for aquaculture products with supply. It would appear to be in their interest to create inclusive arrangements for groups or areas which house producers in their supply chains. However, supermarkets are only likely to support such changes to their supply chains if they have adequate assurance of how farmers are organizing themselves collectively to mitigate their shared risks.

The integration of these four components provide a basis for the ongoing research agenda of integrated approaches to mitigating production risk and producer vulnerability in Southeast Asian aquaculture production.

The SUPERSEAS project, led by Wageningen University and the WorldFish Centre, brings together a consortium of public and private partners working on sustainable aquaculture in Southeast Asia. The first research findings have been submitted to peer reviewed journals and are expected to be published later this year.