Robust policy needed to counter growing inequality and malnutrition across the globe

To ensure global food supply into the future, governments must formulate sharper and more robust policy to counter inequality and climate change. Scenario studies demonstrate that failure to act is likely to lead to increased inequality, malnutrition and instability caused by worsening climate issues.

Research into various causes of hunger and malnutrition

Hunger and malnutrition are complex problems driven by an array of factors, ranging from individual consumers to national treaties. To identify which policies reinforce food and nutrition security, and which policies are counterproductive, the European Commission financed a large-scale research programme entitled FOODSECURE five years ago. The programme involved pioneering research into the various causes of hunger and malnutrition. Alongside exploring the effects of instable food prices on the confidence of African farmers in their investments, it looked at the the key role played by democratic transitions in reducing child mortality linked to malnutrition, the importance of coordinating donors and recipients of financial aid and the structural effects of international trade deals. Besides this, researchers developed future scenarios of potential global developments until 2050 and the number of people still going hungry in these scenarios.

The FOODSECURE Navigator

The researchers used the knowledge gathered during the programme to create the FOODSECURE Navigator, an online toolbox that helps policymakers see the bigger picture. ‘Policymakers tend to focus on their own policy area, but it's also important to look at the relationships between nutrition, agriculture, energy, climate and economics,’ says Thom Achterbosch from Wageningen Economic Research and member of the coordinating team. Given the swift changes in African, Asian and Latin American food systems, interventions and investments in agriculture or nutrition are more likely to have the desired effect if they are informed by a sound knowledge of the economic, social and political context. ‘The FOODSECURE Navigator deciphers the indicators and causes of food insecurity and demonstrates how policies can influence this complex dynamic.’ EU and non-EU policymakers can use the Navigator to compare their vision of the future with that of other stakeholders. They can test their policy ideas for eradicating hunger in two ways: by basing them on evidence of the effects of past policy and on potential developments over the coming decades.

Launched in 2012, the five-year research programme FOODSECURE was assigned a budget of 10.5 million euros, 8 million of which was from the European Commission. The programme aims to improve the effectiveness of EU policy for food and nutrition security, as well as the policy of other governments in Africa, Asia and Latin America in their respective countries. Wageningen Economic Research coordinated the programme, which was joined by tens of researchers from 19 different institutions in Europe as well as China, Ethiopia and Brazil who produced more than 100 scientific publications.

Vision for food security

The cross-institution programme did something never before seen: it also involved tens of stakeholders from the business community, government and NGOs in workshops lasting several days, during which participants brainstormed the complex issue of food security. These meetings produced a vision for food security with new concepts and frameworks for the research. ‘Our most important contribution is the way in which we have changed how people look at food security,’ says project leader Hans van Meijl from Wageningen Economic Research. In its considerations of what causes hunger, FOODSECURE not only looks at the availability of food as governed by technical, economic and biophysical factors, but also focuses on food access by comparing the incomes of people from various income brackets with the price they pay for food. Almost all current long-term studies into climate and food security neglect this crucial dimension of food security.

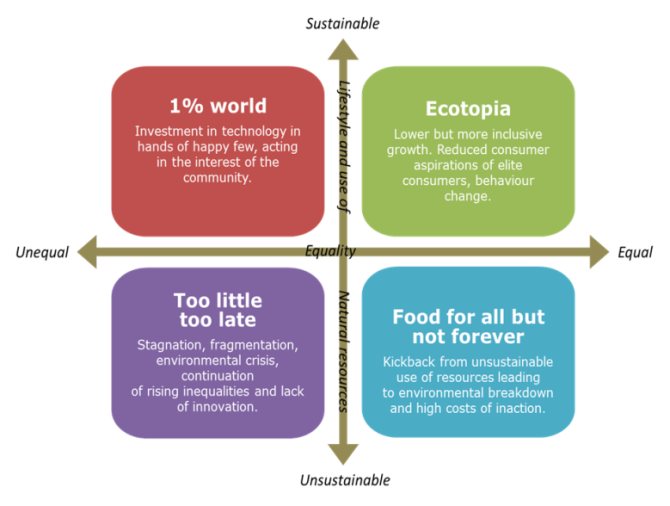

Levels of education, mobility, income distribution and consumer behaviour all play influential roles in this dimension, as shown by the indicators used. As people in Africa purchase on average around 60 to 70% of their food at the market, the purchasing power of poor households is a much more telling measure of somebody's food security than purely the supply of food in an area. ‘One change brought about by the stakeholders’ consultation was particularly significant. In contrast to earlier models, ours was not only based on climate change and sustainability, but also on economic inequality,’ says van Meijl. Inequality and sustainability now form the framework that stakeholders used to develop four future scenarios within the FOODSECURE programme.

Four plausible future scenarios for global food security

At this moment in time, the world is heading for the less sustainable and more unequal scenario. The stakeholders taking part in FOODSECURE expect we will have done ‘too little, too late.’ This scenario involves several financial crises resulting in low economic growth, a huge gap between rich and poor, poor agricultural harvests, marked climate change and a widespread loss of biodiversity. The ‘one-percent’ world is more sustainable. Although wealth is unequally distributed and the rich own the majority of natural resources, investments in research will solve global environment problems and ensure that agricultural harvests remain healthy. Another variant is the scenario ‘Food for all but not forever,’ in which consumption and economic growth are more important than sustainability and bumper agricultural harvests nosedive as a result of environmental crises. The last scenario of ‘Ecotopia’ sees an equal distribution of wealth and more sustainable consumption patterns brought about by diet changes. New forms of sustainable agricultural technology, and in particular more sustainable consumer choices, will eliminate waste, limit greenhouse gas emissions and lead to higher agricultural harvests and better environmental protection.

It should be remembered that the results from the models are based on assumptions, says Achterbosch. ‘These are not hard predictions, so we need to be cautious about the results from the models. However, it is still a way of focusing attention on and encouraging discussions about causal connections and relationships.’ The point that van Meijl and Achterbosch are making is that Ecotopia is not a scenario we will arrive at effortlessly. ‘Almost all scenarios have the real possibility of a growing gap between higher and lower incomes, or of large groups of city dwellers and rural communities who are excluded from economic growth,’ says van Meijl. ‘Our economic system encourages inequality by enabling capital, technology and the rich to take up an ever larger proportion of the extra income earned.’ Poverty leads to hunger and poor nutrition, which in turn feeds inequality. This mechanism is visible today: many countries, particularly in Africa, are experiencing high economic growth in parallel with a growing number of people experiencing food insecurity. The vast majority of economic decisions also bypass environmental and climate effects, as these effects are not automatically reflected in our prices. ‘The conclusion is that more forceful policy must be introduced to counter climate change and inequality. The market will not do this on its own,’ says van Meijl. ‘There needs to be more guidance, and not only from a government level. Companies and consumers can also influence the route we take.’

A recommendation from the research is to strengthen the exchange between science and politics in this area by establishing a new intergovernmental panel on food and nutrition security, just like the IPCC for climate research.

Agriculture is a serious risk for food security

This is in large part a response to the current situation, in which many policy areas with various aims threaten to compromise each other and lead to trade-offs. However, ensuring synergy between policy measures is no easy task. And if we are to reach the climate goals in the Paris Agreement and the ambitious target of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees, then agriculture must do its part in reducing emissions and storing carbon. Reforestation and bio-energy are currently the main drivers in this respect, but the way in which they take up valuable agriculture land poses a serious risk for food security. Food-waste reductions, technological improvements and diet changes (e.g. less meat) have multiple benefits, as they can have a positive effect on the climate as well as food security. Formulating coherent policy for food security remains an important theme within the EU, too. Incoherence in EU policy persists, although the researchers no longer point to EU agricultural policy as the cause. Unlike before, the current European system of agricultural subsidies has hardly any demonstrable impact on food security by disrupting the global market. The bilateral trade treaties currently in place between EU and countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America have varied effects. Generally, these agreements lead to limited export and revenue growth and have a negative impact on local producers and government revenues from import levies. Achterbosch explains, ‘As the agreements bring no great benefit to these regions, they are ultimately unfit for purpose.’ The EU still has a major negative effect on food security in other parts of the world as a result of its enormous contribution to climate change and the way in which it occupies agricultural land elsewhere in the world to feed its consumption pattern and huge imports of soya, palm oil and other tropical commodities. However, within value chains, these trade flows can generate revenue and innovation and strengthen local food security.

Policymakers can use FOODSECURE to learn which policy areas require action to get to a desired situation or development path. Achterbosch adds, ‘The extent to which countries take action to stimulate entrepreneurship, innovation and technology plays a decisive role in improvements to agricultural productivity. Countries can try to limit their population growth by strengthening the position of women. Additionally, they can attempt to influence consumer behaviour, such as by encouraging them to eat less meat. A logical progression is to analyse the expected effects of policy on long-term food security, but this will call for a high degree of detailed knowledge and follow-up research within the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in its programmes on climate change and healthy diets in Nigeria, Bangladesh and Vietnam.

Focus on health factor and evaluate

FOODSECURE differentiates between the short and long term. Short-term measures to combat inequality include a ‘cash for work’ programme or another form of social security, while mid-term measures could involve a differentiated tax system that imposes higher taxes on the middle class than on poor households. Finally, long-term measurements could include investments in education and innovation to enable more people to improve their income. Using the knowledge in the FOODSECURE Navigator, policymakers can weigh up the short-term and long-term effects. ‘Although a food-producing country can counter an acute food crisis as a result of drought, for instance, by imposing an export tax to halt food exports, the resultant lower price of food in the long term will disincentivise farmers from investing,’ explains Achterbosch. A recommendation from the researchers is to ensure the EU focuses more on the health factor in the many billions it gives in aid for food security, and to effectively evaluate the results of this.